Introduction

From a young age, I recognized my family’s deep-rooted identity in the state of West Virginia. Spending summers and holidays there not only granted me a deep appreciation for the beautiful rolling hills, it developed in me the values of caring for family and working hard. As I grew older, I quickly realized that holding these values were not coincidental; they stem from my West Virginia background.

Since the 19th century, West Virginians have been victim to the corporations that exploit them. The coal industry has been allowed to consistently disregard basic human rights in their practices out of a hunger for money and power. Big pharmaceutical companies, in the same way, have successfully used West Virginians for profit– sparking one of the most severe opioid epidemics in the world. My family, on both sides, has been in the coal industry for generations. My great grandpa was an Italian immigrant who found opportunity in a coal mining job. My grandpa worked in the mines all his life. My dad, a first generation college student, works tirelessly at his job everyday and I strive to do the same. Early on, I learned the toll opioid addiction has taken on my cousins living in West Virginia; either from their parents’ neglect or battling addiction themselves. On both sides, my family continues to struggle with the consequences of addiction. The coal and opioid industries have brought pain and suffering to my family for years and its effects only continue to worsen. This project is intended to allow outsiders to understand contemporary West Virginia’s struggles and how they did not appear from nowhere. I will address how both the coal and drug industries within the state of West Virginia have left lasting, generational impacts that require further attention and examination.

My literature review will examine the current plight of West Virginians in three sections. First, I will describe how West Virginians can often be misrepresented, allowing society to lack understanding of the issues that consume them. Second, I will describe the relevance of the coal industry in West Virginia by explaining its history and the lasting damage it caused. Finally, I will explain how Big Pharma has consistently hurt the state and its people.

Literature Review

Understanding Perceptions of West Virginian and Appalachian Culture

West Virginians hold values in family, hard work and perseverance. However, too often West Virginians have been misrepresented in outside portrayals of the population. To understand West Virginians’ reality, we must first understand the perception of the area. The lazy “hillbilly” stereotype promotes an ideology that alienates the rural population of the southern Appalachian mountains. Like any stereotype, outsiders can believe it as true for all, only granting more leverage for abusive corporations.

Appalachia and Appalachian Otherness

William M. Bauer and Bruce Growick state: “According to the Appalachian Regional Commission (ARC), Appalachia is defined as a 200,000-square-mile region that follows the spine of the Appalachian Mountains from southern New York to northern Mississippi” (2003, p.18). Appalachia consists of all of West Virginia and parts of 12 other states.

The definition of Appalachia is not simply based on the geographical region, however. Henry D. Shapiro’s book, Appalachia on Our Mind: The Southern Mountains and Mountaineers in the American Consciousness, 1870-1920, describes Appalachia as not only a geographical, cultural area characterized by the American imagination, but also an abstraction shaped by external perceptions of the region (1978). These abstractions are created in part by cultural influence. Through literature and other modes of popular culture, Appalachia is portrayed as culturally backward, isolated and out-of-touch with contemporary society. Historian Ronald L. Lewis, paraphrases Shapiro (1978), saying:

Fashioned by the local colour writers at the turn of the 20th century to entertain a rapidly urbanising middle class of leisure readers, the caricature persists because it serves to reassure the urban middle class of its cultural superiority (quoted in Lewis, 1992).

The ethnicity of Appalachian people made it easier for the rest of American society to “other” the population–that is to view them as not fully part of America. During the late 1800s, many shunned by American society, and therefore finding it challenging to find consistent jobs, filled demanding coal mining positions. National Park historian Harry A. Butowsky says:

Coal operators were forced to recruit labor from three sources: white Americans from older coal regions, black Americans from the south, especially Virginia and North Carolina, and immigrants from Southern and Southeastern Europe (1994).

America’s consideration of American blacks post-Civil War and immigrant Anglo-Saxon whites as alien to the current American society, facilitated the idea of the general Appalachian population to be “un-American” for years to come (Shapiro, 1978).

Historically, Appalachian otherness began with northern Protestant churches considering the region as “unchurched” because their denominations were not represented there (Shapiro, 1978). Religious formations in the region were typically home-missionaries.

The alleged absence of schools and churches in the mountains, moreover, constituted at once a clear indicator of the nature of Appalachian otherness and an adequate explanation for why mountaineers seemed so ‘behind the times’ (Shapiro, 1978, p.33).

For years, Appalachia generally abstained from Protestant denominations. Even when the church expanded from the north to southern states after the Civil War, southern mountainous areas remained independent in their religious practices. This reality was eventually accepted by denominational church communities. However, along with a combination of local colour writers promoting Appalachia as “a strange land with peculiar people,” it further institutionalized its people as in, but not of, American civilization (Shapiro, 1978).

Consequently, Appalachian and West Virginian people became associated with the “hillbilly” stereotype that persists to this day. As explained by author Anthony Harkins, “hillbillies” have often been portrayed as shiftless, drunken, promiscuous, and bare-footed people, living in blissful squalor beyond the reach of civilization in mass media (2004).

‘Hillbilly’ is no different than dozens of other similar labels and ideological and graphic constructs of poor and working-class southern whites coined by middle- and upper-class commentators, northern and southern (Harkins, 2004, p. 6).

Presenting southern mountain folk as foolish to the modernization of the rest of society, diminishes the realities and struggles of the poor, industrialized area.

Rather than attempting to understand the qualities of mountain life and elements surrounding mining communities, Americans created outside sociological perceptions of the region to continuously justify public misrepresentation. The lack of desire to comprehend why Appalachian culture seemed disparate to the rest of society added to this. Negative cultural imagery still dismisses West Virginians’ struggles caused by their geographical location. This portrayal not only reaches mainstream Americans: it also conveys these ideals back to Appalachians themselves, damaging their sense of self-esteem and value to the world, resulting in what Tommy M. Phillips calls “Appalachian Fatalism.”

Appalachian Fatalism

Faced with poverty, high addiction rates, corporate exploitation and negative cultural representation, residents of Appalachia often fall victim to Appalachian fatalism, a mindset which the Appalachian people tend to live their life day to day, giving little thought to the future (2007). Under this sociological doctrine, Appalachians often believe they are destined for hopelessness and disparity. This causes a lack of motivation to find new pathways in life when they feel stuck in the same cycle.

This mindset can be traced to the socioeconomic foundations on which the region was built. Appalachia, originally reliant on the coal industry to fuel its economy, saw consequences of this dependence early on. Researchers Loretta R. Cain and Michael Hendryx explain:

Coal mining areas of Appalachia are characterized by persistent levels of low educational attainment rates and high rates of poverty and these conditions in return relate to poor cognitive development in children (2010, p. 71).

According to Cincinnati Children's Hospital, “cognitive development” is the developmental stage where children learn to think and reason. Adolescence is the stage at which people form more logical and complex thinking processes (2024).

In 2007, Phillips conducted a study finding that young Appalachian adolescents possessed more fatalistic identity processing qualities than those of non-Appalachian adolescents. Using a Likert-type scale, Dr. Phillips created statements that would score the participants’ identity styles using M.D. Berzonsky’s three categories: informational, normative and diffuse-avoidant. An obvious association with fatalism and the “diffuse-avoidant” style was observed by Appalachian teens. The “diffuse-avoidant” identity style–the least adaptive of the categories examined– is defined as procrastination and avoidance of dealing with personally relevant issues (Phillips, 2007). Having this inherent mindset is detrimental to the stage of adolescence. Adolescents may find it challenging to imagine a better future for themselves if they are feeling hopeless.

Results of Phillips’ study displayed most of the differences in responses between Appalachian and non-Appalachian teens were in questions that were cultural rather than socioeconomic.

The higher mean diffuse-avoidant score of the Appalachian participants was probably a direct corollary of a cultural setting characterized by fatalism, a setting that would be expected to preclude active exploration and navigation of identity issues as a result of the prevalent belief among Appalachians that events are fixed and people are powerless to change them (Phillips, 2007, p.15).

This means that the Appalachian adolescents’ fatalistic response to the questions appeared largely attributed to their culture. Whether beliefs about their culture presume to be coming from external or internal views is not specified. However, internal or not, cultural generalizations have allowed the Appalachian youth to absorb the idea that their identity and future is fixated. From an outside perspective, expectations are low, causing feelings of alienation in society and perpetuating these notions generationally.

West Virginians’ Perspective

Appalachian youth are not oblivious to cultural conceptions of their identity. In author Christine Ballengee-Morris’ “Hillbilly: An Image of Culture,” she interviews Appalachian students K-12 about stereotypical images resulting from where they live. One of the top five reasons Ballengee-Morris found for students wanting to leave their region was to make themselves a more “positive, accepted image because I don’t want to grow up and be Elly May [a main character in the popular TV show: The Beverly Hillbillies (1962-1971)]” (2000).

Despite negative connotations around the construct, over time, the ‘hillbilly’ has been embraced by Appalachians.

Many southern mountain folk, often trapped in regional low-paying industrial work or forced to migrate outside the mountains to survive, embrace elements of both the rugged and pure mountaineer myth and the hillbilly label and it’s implied hostility to middle-class norms and propriety (Harkins, 2004, p.5).

In 2006, Cathy A. Coyne et al. examined Appalachian adults in their study about social and cultural factors influencing southern West Virginia. Participants had a positive reaction to the term hillbilly and were more hesitant to accept the term Appalachia except when referred to solely as a geographical location.

Participants blamed the media's sensationalism for the establishment and perpetuation of negative Appalachian stereotypes. They felt stereotypes are conceived by people with little knowledge of the area's geography and culture. Participants felt that the derogatory meaning of stereotypes and the fact that negative images of West Virginia are not balanced with positive ones are what hurt people (Coyne et al., 2006).

In this study as well as in Bill Barker’s: “A Study of West Virginia Values and Culture” (2004), West Virginians report overwhelmingly positive values surrounding the state’s culture. Some of the values Barker mentions include:

Traditionalism or Heritage

A strong sense of family, or “Familism”

Strong Religious Beliefs

Love of the Home Place

Neighborliness and Hospitality

Individualism, Self-Reliance, and Pride (2004, pp. 6-12)

West Virginians are typically proud of where they came from. Southern mountain life and the culture surrounding it adds to their sense of belonging rather than bolstering feelings of isolation. Possessing values of heritage, familism, and hospitality reflect a strong sense of community. Through shared understanding, West Virginians consolidate because of the obstacles they have faced from corporate powers and the negative connotations against them. For generations, they have remained strong. Even when feelings of hopelessness consume them, they unite.

The othering of Appalachians and, consequently West Virginians, to the rest of the world which portrays them as less intelligent or less competent, hurts their reputation as they struggle against profit-driven corporations. These attitudes have allowed corporations to take advantage of a place already viewed negatively by the general population of America.

The Coal Industry’s Influence on West Virginia:

Hopelessness and fatalism do not arise from nowhere. In this section, I will describe how the coal industry influences historical, sociological, economic and environmental issues within West Virginia. Since the beginning, the industry has exploited West Virginians and the industry, present-day, continues to disregard the best interest of citizens affected.

History of Coal Mining in West Virginia

Although coal was first discovered in West Virginia in 1742, according to the WV Geological & Economic Survey, mining didn’t begin until the mid-1800s. In 1863, West Virginia became an official state of the United States. In a new world searching for new resources, the mountains quickly displayed their potential.

Historian Harry A. Butowsky explains the importance of coal in West Virginia labor history:

Paramount in the region's economic history, the coal industry has been of critical importance in the development of the national industrial economy. Historically, West Virginia and Virginia coal has been widely considered as unsurpassed in quality (1994).

Coal generated an abundance of jobs. The Industrial Revolution in the US brought immigrants flooding to all areas of the country in search of The American Dream: Many settled in the valleys of West Virginia and Kentucky to work in the mines (Butowsy, 1994). Over a century later, we see an industry now shunned for its unsustainable and nonrenewable qualities, struggling for vitality. But it is not the industry itself we care about; it is the people who have been working for the industry since their families arrived in America generations ago.

The coal mines, even in their economic prime, were never a good place to work. Most men worked over 12 hours a day, finding little forgiveness from coal corporations seeking profit.

Driven by shared struggles and concerns, miners banded together to create unions starting in 1890. For almost 130 years, United Mine Workers of America (UMWA) has allowed miners to come together in solidarity over pressing issues within their respective coal communities.

Harsh working conditions in the mines caused many organized strikes at coal companies. According to historian Hoyt N. Wheeler, the first notable ongoing miners strikes in West Virginia took place in 1912 to 1913 at Cabin Creek and Paint Creek. Miners at both Paint and Cabin Creek came up with their series of demands, presenting them to their respective coal companies. Miners' demanded basic human rights such as: rights of free speech and peaceable assembly, an end to compulsory trading at company-owned stores and increased wages. Within days, the coal companies rejected these demands, so the miners struck (Wheeler, 1976).

Coal companies implemented an assault campaign, hiring mine guards. The guards began evicting miners and their families from their company-owned homes, tossing their belongings and leaving many homeless. A series of brutal battles between coal operators and coal miners continued for months including one notoriously known as the ‘Bull Moose Special.’ Organized by the Sheriff of Kanawha County, this horrific attack entailed shooting hefty rounds of rifle and machine gun fire into miners' tent colonies– killing one and injuring several. The violence and the strike eventually ended after Dr. Henry Hatfield was elected as governor of West Virginia.

The Governor disapproved all of the sentences of the military courts, and decreed that the miners should get much of what they had asked for…the miners had obtained a modest increase in wages, the right to a check-weighman, and a temporary respite from forced trading in company stores (Wheeler, 1976).

Likely the most violent of mine wars in West Virginia took place in Mingo and Logan counties in 1920-1921. These two counties’ miners met in Marmet to demand their wages be returned to normal after a massive cut. “An investigation was made, but the State Legislature, which was dominated by the coal operators, failed to take any action to alleviate the deplorable conditions found by the investigators” (Wheeler, 1976). Many were fired for suspected union participation in Mingo county. An official strike began on May 19, 1920. Months of violence ensued between coal operators and their miners.

The causes of the violence arising out of the union's attempts to organize miners in Mingo and Logan Countries range from economic conditions in the nation as a whole to the eviction of miners’ families from their homes in remote mountain hollows (Wheeler, 1976).

Dependency of miners on their coal companies because of company housing and required spending at the company store, made it challenging to live free of corporate control for years in miner history.

Even though miners continuously unionized and protested against the corporations harming them for decades, the coal industry continues to exploit the West Virginian people.

The Socioeconomic Impacts of the Coal Industry on West Virginia

Since the 19th century, coal has had a massive hold on West Virginia. The coal industry has continued to mold, change and technologically advance in a way that consistently favors profit over West Virginians. West Virginians are victims to what sociologists Bell and York call the “treadmill of production” (2010), in which negative processes like extraction (of coal) and degradation (of the land) will continue as long as they generate profit. Over the years, Bell and York observe this treadmill accelerating as technologies have advanced. The more technological advancements the industry finds, the more people are left jobless and poor as coal corporations continue to become wealthier.

West Virginians have attempted to stand up to the environmental crimes against them. Groups like “Coal River Mountain Watch,” a non-profit, grassroots organization created in 1998, have conducted peaceful protests to call out coal corporations for their mistreatment of the community’s people and environment.

Even as these groups arose, however, pro-industry groups pushed back. For instance, Friends of Coal is a countermovement pushing back against social, environmental groups protesting coal’s negative impact on West Virginia communities. Started by the West Virginia Coal Association in 2003, the Friends of Coal mission aims to uphold pride in the coal industry as it has a “vital role in the state’s future” according to the organization’s website.

By spreading its message with a heavy presence in West Virginia communities, Friends of Coal still claims the coal industry as still possessing a reliable job market and remaining vital to the state’s livelihood. It is indisputable that, for decades, a recognizable, steady decline in coal mining jobs has manifested– seen in the figure provided by ClimateNexus in 2019:

Friends of Coal amplifies the supposed reliance on coal by infiltrating propaganda into communities.

Through our content analysis and field observations, we found that the Friends of Coal employs two strategies to do this: (1) by appropriating West Virginia cultural icons; and (2) by creating a visible presence in the social landscape of West Virginia through stickers, yard signs, and sponsorships (Bell and York, 2010).

The organization feeds off the idea of no other industry being tied so closely to the identity of a state as coal to West Virginia in American culture. Of course, West Virginians have identified with the coal industry for generations. However, Friends of Coal uses this by presenting coal as continuously essential for West Virginia to remain confident in its statehood. But, just because West Virginia’s coal industry may cease to exist, that doesn’t mean its people will.

Health & Environmental Impacts of West Virginia’s Coal Mining

Along with causing social and economic instability, the coal industry directly harms the health of West Virginians. Coal extraction has changed and advanced drastically since its inception, often bringing new health hazards. The 1980s brought new mechanical advances that transformed the extraction process. Mountaintop removal is one of the easiest factors to pinpoint the destruction of the physical environment of West Virginia.

Investigated in Bill Haney’s documentary “Last Mountain” (2011) and Michael O’Connell’s documentary “Mountaintop Removal” (2021), mountaintop removal is a surface mining extraction process in which explosives are used to access the core of a mountain’s coal supply. This is the fastest, most efficient coal extraction process. “Mountaintop Removal Mining has destroyed 500 Appalachian Mountains, decimated 1 million acres of forest, buried 2,000 miles of streams, and is contaminating thousands of miles more” (Haney, 2011). It causes a multitude of consequences to the land, including flooding as a result of deforestation. Without trees to stop water flowing into valleys, polluted water continuously floods the homes of innocent people.

Some issues created by mountaintop removal include “coal-sludge dams” or “slurry impoundments.” Coal-sludge dams contain coal waste caused by extraction. According to author Elizabeth Winterhalter, on February 26, 1972, three of these slurry impoundments burst, flooding Buffalo Creek hollow with toxic black sludge, killing 125 people and leaving even more homeless (2021). Another waste “removal” method practice is the injection of waste into abandoned mines (Bell and York, 2010). This practice causes well contamination, leading to health issues like liver and kidney cancer, skin disorders, organ failure and more.

Mountaintop removal is a form of surface coal mining. Surface coal mining, past and present, causes local air and water pollution in the Appalachian region. Researcher Micheal Hendryx conducted a series of epidemiological studies indicating “significantly higher hospitalization rates for hypertension and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease as a function of tons of coal mined” (2015). This study showed a positive correlation between people in counties with more surface coal mining being more likely to be hospitalized for these reasons.

Although harder to link direct health impacts to, water pollution shows to negatively impact the health of those in areas where surface mining is prevalent. In Haney’s “Last Mountain” (2011), Dr. Ben Stout explains on screen that he tests the waters near these mining sites, often finding heavy metals such as lead and arsenic in the streams that flow from surface mining sites into the hollows where people live. These are areas where people rely on wells as their water source and surface mining has completely contaminated them (Haney, 2011). The documentary looks into a small community called Prenter, West Virginia, where six brain tumors within less than a mile radius resulted. The water filters for their wells that supposedly last 2-3 months have to be changed every two weeks (Haney, 2011).

Before surface coal mining was the primary process of extraction, West Virginians went into mines to dig for coal manually. According to author Lorin E. Kerr, being inside shallow mines for all hours of the day led to the excessive inhalation of the harmful coal-mine dust called silica. The inhalation of silica causes the coughing up of black ‘spittle’ and a blackish tint to the lungs. This is a disease we know of as “black lung” or “coal-worker’s pneumoconiosis (CWP)” (1980).

The black lung disease comes with a long history of avoidance. Coal mining went on for hundreds of years in Europe before it was first mentioned as a disease in the mid-1800s. America took longer to accept its fatality (Kerr, 1980). Call to action for federal law was generally out of play until November 20, 1968, when the nation first witnessed the devastation of a West Virginia mine explosion on television. 78 miners were killed outraging Americans to push for federal law towards miners’ compensation.

The clamor wiped out long-standing barriers which the pleas of the miners and their union had previously been unable to tear down. The public and Congressional campaign to try to eliminate the daily toll of coal-mine accidents soon included the equally destructive losses due to dust disease (Kerr, 1980, pp. 54-55).

In southern West Virginia, 40,000 miners walked out of the mines to demand the passage of a bill to make coal workers’ pneumoconiosis a compensable disease. Accordingly, the Federal Coal Mine Health and Safety Act of 1969 was passed, including a section titled “Black Lung Benefits”; notable because it was the first time black lung was federally recognized as a real disease caused by inadequate working conditions (Keer, 1980).

However, this act came with a lot of flaws in actually providing compensation to miners. Benefits would typically not be made until after someone stopped working in the mines and they were virtually disabled by the disease. Only a fraction of cases were ever approved.

A General Accounting Office study indicated that the average length of time for processing a claim was 645 days. In the four years between July 1, 1973, and early 1977, the Department of Labor received more than 106, 700 new black lung claims of which about 53,500 were disallowed and 49,200 were pending. Only 400 claims had been approved (Kerr, 1980, p.58).

Some improvements were made with the 1978 Black Lung Benefits Reform Act passed by Congress, removing some of the preventative restrictions on providing compensation.

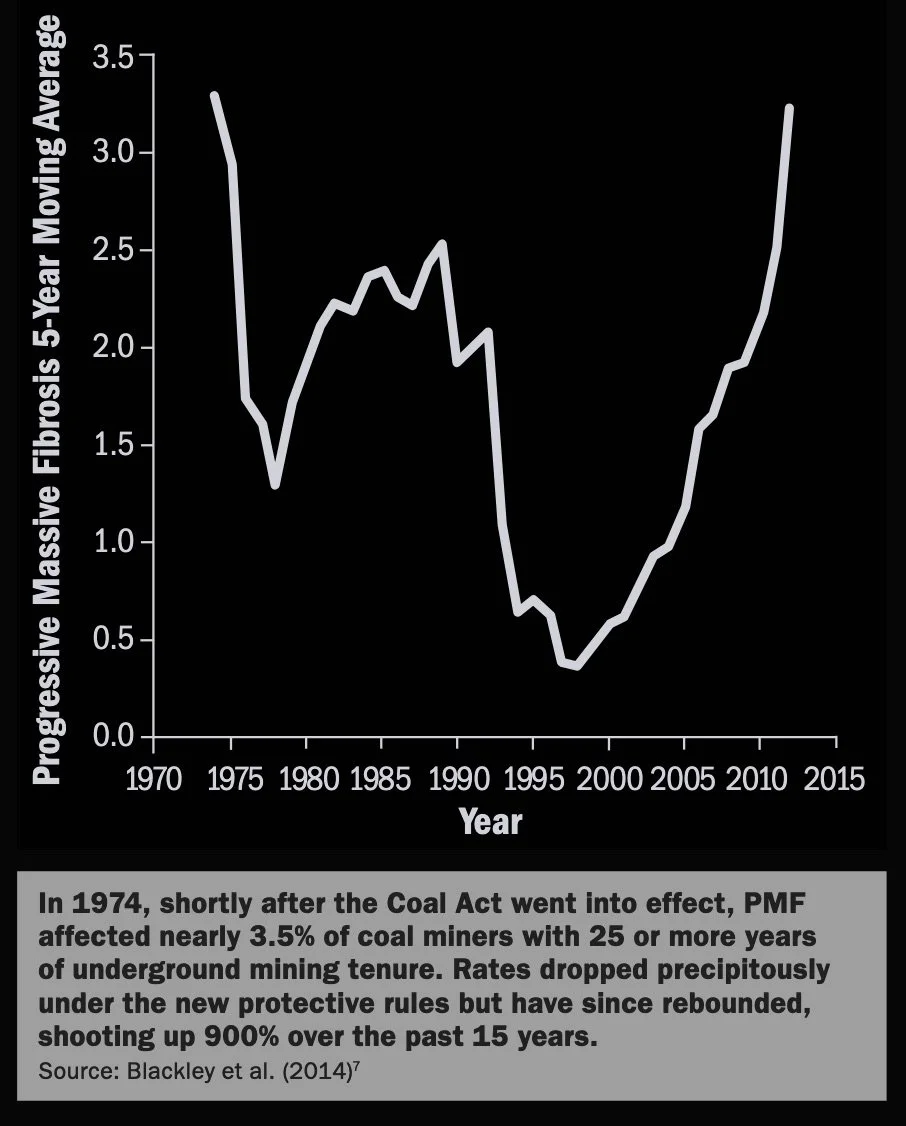

According to science writer Carrie Arnold, as of the mid-1970s, black lung affected around one-third of miners who had worked in American underground mines for more than 25 years (2016). Mines began working towards creating better ventilation for miners, but the disease resurged in the early-2000s– exposing a more recent neglect in coal industry practices.

Since coal mining began in America, it has remained challenging for miners to receive proper compensation for the handicaps provided by the industry. Disease and work injury have plagued miners as a result of “mining the nation’s vitally needed coal” as stated by Kerr (1980, p.60). Miners have been the ones paying the price while coal corporations profit.

In a similar way, Big Pharma has used miners’ misfortunes to make money. The overprescribing of strong, addictive opioids for chronic pain resulting from work injury progressed the opioid epidemic seen in West Virginia today.

Big Pharma’s Influence on the State of West Virginia

Just like the coal industry, Big Pharma has advantageously used the population of West Virginia for its own profit. In this section, I will first briefly describe opioids and how they came to be so prevalent in America’s pharmaceutical industry. Then, I will describe how this history led to the increased prescribing of opioids, targeting places like West Virginia. Big Pharma has created an opioid epidemic in the region that is also attributed to an increased usage of other synthetic opioids such as heroin and fentanyl.

A Brief History of Opioids

Opium, extracted from the poppy plant, was first used by the Egyptians. In the present day, in its synthetic form, opium is used to medicate pain, as explained by the narrator of Alex Gibney’s two-part documentary The Crime of the Century (2021). Synthetic opium was first created and distributed as a prescription drug by The Merck Company in 1827, under the brand name ‘morphine.’ Then, in 1898, Bayer, a German pharmaceutical company, produced a cough suppressant they named ‘heroin’ (Gibney, 2021). When heroin showed to be highly addictive amongst the mass population, the United States made it illegal in 1924. The narrator of Gibney’s film explains:

Big pharma turned to the mass manufacturer of other opium products like morphine and oxycodone and learned how to mechanize the process. They created a demand for narcotics, addicting millions of men, women and children which, in turn, fueled the illegal drug trade (2021).

Since the early 20th century, big pharmaceutical companies and the illegal drug trade have been intertwined, generating $100 billion in profit per year combined. Over the last two decades, 500,000 Americans have died from opioid overdose explicating a deadly business model (Gibney, 2021).

The Sackler family changed the way pharmaceuticals are sold in America. After their purchase of what was called Purdue Frederick, a small pharmaceutical company, in 1952, Arthur Sackler purchased a medical advertising company called MacAdams. “Arthur Sackler was a pioneer in bringing Madison Avenue techniques to the selling of drugs. But in doing so he often crossed the line from promotion to fraud” (Gibney, 2021). Arthur Sackler often paid doctors to promote the selling of his drugs to other doctors.

He paid a division head at the Food and Drug Association (FDA) to do the same (Gibney, 2021). Sackler pushed drugs produced by Purdue Pharma like Librium and Valium to doctors to treat everyday anxiety patients. When those drugs were found to be highly addictive, Sackler pushed the idea that the drugs weren’t the problem, the patients were (Gibney, 2024). Arthur Sackler died before the creation of OxyContin. However, he created the foundation that allowed his family to spread corruption for profit in the pharmaceutical industry for years to come through medical advertising and victim blaming.

Purdue Pharma released MS Contin in 1984, a morphine pill typically used to treat the pain of cancer patients. When generic versions of MS Contin began entering the market, Purdue looked into the usage of oxycodone, an opioid stronger than morphine. This idea produced OxyContin: oxycodone hydrochloride controlled-release tablets.

In 1994, Purdue started its FDA application for the approval of OxyContin. The diction of the application minimizes the addictive nature of the drug. They list it as being for any non-cancer pain patient with chronic, moderate to severe pain, allowing the sale of the drug to reach the largest audience possible (Gibney, 2021). The Sacklers looked to Dr. Curtis Wright, a medical review officer at the FDA, to approve their application in the way they wanted. A document from a Non-Disclosure Agreement (NDA) was leaked to Gibney and his production crew, showing that with Wright’s help, Purdue drafted their review to promote the notion that OxyContin does not signal being addictive or easily abused.

Purdue executives camped out for three days in a rented room near Wright’s office and worked with him to draft the official FDA review of OxyContin in a way that Wright promised would be promptly approved (Gibney, 2021).

Wright was hired by Purdue Pharma a little over a year after approving OxyContin on the FDA’s behalf.

Now, a drug stronger than morphine, and synonymous to heroin in a pill, is used to treat a wide range of ‘pain’ patients.

The 1996 introduction of OxyContin coincided with the moment in medical history when doctors, hospitals, and accreditation boards were adopting the notion of pain as ‘the fifth vital sign,’ developing new standards for pain assessment and treatment that gave pain equal status with blood pressure, heart rate, respiratory rate, and temperature (p.27).

As stated in Beth Macy’s Dopesick (2018), she explains how promotion of pain as “the fifth vital sign” during the time of OxyContin’s release contributed to the widespread acceptance of the drug by medical professionals. Purdue Pharma and the Sacklers immediately used this to their advantage. In his article for The New Yorker titled “The Family That Built an Empire of Pain,” journalist Patrick Radden Keefe wrote:

In 1997, the American Academy of Pain Medicine and the American Pain Society published a statement regarding the use of opioids to treat chronic pain. The statement was written by a committee chaired by Dr. J. David Haddox, a paid speaker for Purdue (2017).

Through Arthur Sackler’s legacy, the Sackler family has continuously used their wealth to optimize profit in corrupt business practices. By paying medical professionals, they pushed OxyContin as a sound treatment for pain, no matter lacking proper research on its addictive qualities.

Big Pharma in West Virginia

“Appalachia was among the first places where the malaise of opioid pills hit the nation in the mid 1990s, ensnaring coal miners, loggers, furniture makers and their kids” (Macy, 2018, p.16). An increase in opioid addiction and overdose in West Virginia was first seen in 1999, four years after OxyContin was approved by the FDA. Early on, it became clear to big drug distributors that places like West Virginia would be an easy target to sell their drugs. Studied by Dr. Marie A. Chisholm-Burns and other contributors (2019) and addressed later by researcher David Kline et al.:

Aggressive marketing across the country of opioids as a safe, non-addictive alternative to treat non cancer chronic pain contributed to the rise in prescription opioid overdoses across the country, while the concentration of deindustrialization, increasingly precarious working conditions, and workplace injuries may have led to a particularly high rise in prescription opioid overdose deaths in places like Central Appalachia (Kline, 2024).

In Central Appalachia where the economy is largely centered around labor intensive jobs, there is a higher presence of work-related injuries. This has allowed for easy exploitation of workforce West Virginians through the overprescribing of OxyContin as treatment for chronic pain.

That was how Debby Preece lost her brother, William “Bull” Preece. After falling off a ladder working at Penn Coal mine, Bull was prescribed OxyContin and Lortab. He overdosed five years later. In Eric Eyre’s book Death in Mud Lick: A Coal Country Fight against the Drug Companies That Delivered the Opioid Epidemic (2020), Eyre tells the story about how this one death led to a State of West Virginia lawsuit against big drug distributors. Eyre is a Pulitzer Prize winning journalist for his investigative reporting with the Charleston Gazette-Mail on the opioid crisis. His investigation uncovered government corruption behind giving drug companies more liberties to push more pills into West Virginia pharmacies.

Lawyer Jim Cagle represented Debbie Preece in her lawsuit against SavRite’s owner Jim Wooley, whose neglect resulted in the death of her brother. SavRite, located in Kermit, West Virginia–population: 294, was making $500,000 in sales. 90 percent of the drugs shipped to the pharmacy were painkillers.

The pharmacy received 3,194,400 tablets of hydrocodone in 2006. Millions of pain pills–Lortab, Vicodin, Percocet–sold to a single pharmacy in one year. The pharmacy had filled prescriptions at a rate of one per minute (Eyre, 2020, p.77).

A plethora of people, either addicts themselves or people who had lost a loved one to prescription drug addiction, came to Preece’s door after her successful lawsuit against Wooley. Preece and Cagle soon realized how big this case could be.

In 2012, former attorney general Darrell McGraw appointed lawyers Jim Cagle and Rodney Jackson his special assistant attorneys general in a lawsuit by the state of West Virginia against Cardinal Health, AmerisourceBergen and a dozen other prescription drug distributors.

McGraw had sued Purdue Pharma in 2001 for the overpromotion and distribution of OxyContin in West Virginia. The settlement resulted in a pittance of $10 million to go towards doctor continuing education programs, law enforcement drug prevention programs and community drug-rehabilitation programs, according to a law review by Joseph B. Prater (2006). This amount hardly covered a fraction of the damage Purdue Pharma had caused in West Virginia as a result of pushing OxyContin into rural communities. McGraw, left embarrassed by the results of this case, awaited another opportunity to hold big drug companies accountable.

However, the attorney general’s office was turned over to Patrick Morrisey in 2013. It quickly became evident that he was attempting to withdraw McGraw’s lawsuit. Eyre discovered that Morrisey’s wife was a lobbyist for Cardinal Health, the largest drug distributor of OxyContin to the state at the time and the lead defendant in the lawsuit (2020). Morrisey attempted to take Cagle and Jackson off the case and assign his own loyalist lawyers to the lawsuit.

After Eyre repeatedly questioned Morrisey’s intentions with the lawsuit and his wife’s role with Cardinal Health, Morrisey initiated war on Eyre and the Gazette-Mail, threatening legal action for libel and defamation.

Even so, Cagle, Eyre and the Gazette-Mail did not cower to Morrisey or the drug distributors he was supposed to be suing on behalf of the State of West Virginia. After Morrisey looked for representation elsewhere in West Virginia’s case against Mckesson–another big drug distributor to the state– Cagle requested that Judge William Thompson unseal a secrecy deal made between Morrisey and several drug distributors.

In late November of 2013, Judge Thompson had ratified a confidentiality agreement between Morrisey’s office and AmerisourceBergen, along with eleven smaller distributors such as Miami-Luken and H.D. Smith. The decree allowed the companies to conceal records and testimony–and perhaps entire pleadings–as the state’s lawsuit against them proceeded. Cardinal Health and Morrisey’s office filed an identical agreement that December (Eyre, 2020, p.117).

These records indicated details about pill shipments by distributors into West Virginia. After a long back-and-forth battle, these records were uncovered, revealing alarming numbers.

AmerisourceBergen alone had distributed 119 million doses of highly addictive drugs to West Virginia pharmacies between 2007 and 2012, or roughly eighty pills for every man woman, and child in the state. About 90 million of those pills were prescription opioids such as Lortab, Vicodin, and OxyContin. The company shipped another 27.3 million tablets of alprazolam or Xanax, the anxiety medication that addicts often took with painkillers. Even smaller wholesalers, such as H.D. Smith, had big numbers–12.4 million hydrocodone pills and 3.2 million oxycodone pills over the same years (Eyre, 2020, p.130).

Pills were shipped to small pharmacies all over the state, fulfilling prescriptions from doctors who were later convicted of federal crimes.

The West Virginia lawsuit came to a settlement of $20 million from Cardinal Health, $16 million from AmerisourceBergen and an additional $11 million allotted from previous settlements from nine smaller distributors (Eyre, 2020). $47 million is obviously not enough to cover the pain and death caused as a result of greedy corporations and corrupt politicians like Morrisey whose office received $8 million of the settlement. However, this lawsuit, and the Charleston Gazette-Mail’s consistent coverage of the case, brought recognition on a federal level, prompting the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) to release detailed records to the public of all the distributors' pill sales.

The drug distributors had saturated America with 76 billion oxycodone and hydrocodone pills from 2006 to 2012. The records provided a road map to the painkiller epidemic nationwide, tracing the path of every prescription opioid manufactured and distributed. The states flooded with the most pills per person per year–West Virginia, Kentucky, South Carolina, and Tennessee–were also ravaged by a disproportionate number of prescription-overdose deaths. Rural counties were hit hard: two in southern Virginia received the highest concentration of pills per person, followed by Mingo County [WV] and nearby Perry County, Kentucky (Eyre, 2020, p.255).

For years, greed drove corporations to push more and more pills into pharmacies, targeting Appalachian states. As Macy put it best in Dopesick: “If fat were the new skinny, pills were becoming the new coal” (2018, p.18). This concentration towards rural, labor-driven communities has created disparities in the opioid epidemic’s effect on West Virginia, conjuring more problems such as heroin addiction and child neglect.

Opioid’s Disproportionate Effect on West Virginia

In their 2024 study, David Kline and other researchers describe a three-wave spike in opioid deaths by individually observing states’ death tolls between the years 1999 and 2021.The three waves present as: a spike in prescription drug-related deaths from 1999-2005; a spike in heroin-related deaths from 2010-2014; and a spike in synthetic-related deaths from 2014-2021. Although Kline et al. were able to pinpoint spike periods in opioid overdose deaths, West Virginia continuously far outstrippedother states in their data. “We find West Virginia was a clear outlier in terms of prescription opioid overdose deaths, with prescription opioid overdose death rates that were more than double those of any other state,” (Kline et al., 2024).

Today, overdose is the leading cause of death for Americans ages 18-44, according to the Centers for Disease Control (CDC). However, Xiwen Huang, MPH, and other contributors, find that opioid overdose, specifically, is more common among individuals born between the years 1947 and 1964, which covers the generation we know as “baby boomers” (2018). According to Huang et al., this is evidently because of higher opioid prescriptions given to older populations. Opioid prescription deaths skyrocketed in 1999 and continue to increase along with heroine and synthetic opioid-related deaths.

Researchers Todd H. Goldberg and Blair Saul studied the aging population of West Virginia describing it as such:

According to the 2010 census, West Virginia has the 4th highest median age of any state at 41.3 (compared to a national median of 37.2), as well as the second highest percentage of older adults in the nation (17.8% over 65, over 320,000 individuals out of a total state population of 1.85 million, compared to 14.1% of the total US population of 319 million). And as the "baby boom" generation ages these trends will only accelerate (US Census Bureau) (2016).

West Virginia has one of the oldest populations in the US. Notably, USAFacts.org found that the state has one of the highest “baby boomer” populations in the country.

The characteristics of baby boom cohorts, including unique vulnerabilities to drug abuse caused by increased use of illicit drugs in adolescence, complicate treatment caused by undiagnosed psychiatric and medical comorbidities and unwillingness to actively seek treatment and might explain their higher death rates from prescription opioid overdose and heroin overdose (Huang et al., 2018).

This age factor exemplifies the increased vulnerability of West Virginia’s population to opioid addiction and overdose.

In recent years, heroin and fentanyl overdoses have steadily increased in West Virginia when prescription overdoses have remained steady. Researchers Jeff Ondocsin and other contributors studied the increased usage of methamphetamines in co-use with heroin in southwestern West Virginia. Each of the subjects interviewed all used methamphetamines with heroine for one of three main reasons: 1) ‘intrinsic use’ –pleasure of combining the two drugs; 2) ‘opioid assisting use’ –claimed methamphetamine use helped manage their heroin/fentanyl use; and 3) ‘reluctant or indifferent use’ –whether it be for lower cost of methamphetamine or easier access to the drug in comparison to heroin (2023). The most notable finding from this study was how the subjects’ addictions advanced.

Among participants where the order of drug progression was clear, all had initiated their opioid use with prescription opioid pills, but had transitioned to heroin after the pills became prohibitively expensive and more difficult to obtain (Ondocsin et al., 2023).

Increased opioid prescriptions, along with the buying and selling of such pills, is actively creating addictions to other harmful, recreational drugs.

In Very Ape’s documentary Oxyana (2017), we see how opioid pills have possessed the lives of the people of Oceana,West Virginia. In an area where addiction is the economy, the prices of pills in the illegal prescription drug trade are high, a 30 mg pill typically ranging between $40-50. Oxyana (2017) interviews multiple subjects who explain the various issues a reliance on pain pills has created in their community. An increase of addiction to heroin and other substances has taken over along with an increase in homicides in the area– suspectedly linked to drug-related altercations.

According to Sara Warfield, MPH, and other experts, West Virginia saw a drug overdose rate of 52.0 per 100,000, 250% higher than the national average of 19.8 per 100,000. Warfield et al. took their studies further, looking at hospitalizations at six different West Virginia Medicine University (WVU Medicine) facilities dispersed around the state for opioid overdose. This means observing unique patients whose overdose did not result in death and/or they were admitted more than once within the last 12 months for opioid overdose. Results from their research presents the issue as not just opioid deaths, but how opioid addiction stands as a problem for struggling West Virginians.

The rate of admission for opioid-related overdoses increased by 181% between 2008 and 2016, from a hospitalization rate of 22.5 per 10 000 in 2008 to 63.3 per 10 000 in 2016. During that time, the percentage of patients with a 12-month repeat overdose increased by 175%, from 10.2% in 2008 to 28.0% in 2016, an average annual percentage increase of 13% (Warfield et al., 2019).

The population of West Virginia is disproportionately victim to opioid overdose in comparison to the rest of the US. “Between 1999 and 2004, the number of West Virginians who lost their lives to accidental overdoses jumped 550 percent” (Eyre, 2020, p.11). This is not because of West Virginians themselves, but because of consequences created by companies seeking profit. Promoting this epidemic to a vulnerable area of the country allowed those in power to easily manipulate the system for their benefit.

References

About Us | Coal River Mountain Watch. (n.d.). Retrieved November 15, 2024, from https://crmw.net/about.php

America is getting older. Which states have the largest elderly populations? (n.d.). USAFacts. Retrieved November 15, 2024, from https://usafacts.org/articles/america-is-getting-older-which-states-have-the-largest-elderly-populations/

American Hollow (Director). (2015, March 7). American Hollow (1999) [Full Movie] [Video recording]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CDAFy3ASNOo

Appalachia on Our Mind | Henry D. Shapiro. (n.d.). University of North Carolina Press. Retrieved November 15, 2024, from https://uncpress.org/book/9780807841587/appalachia-on-our-mind/

Arnold, C. (2016). A Scourge Returns: Black Lung in Appalachia. Environmental Health Perspectives, 124(1), A13–A18. https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.124-A13

Ballengee-Morris, C. (2000). Hillbilly: An Image of a Culture. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED464794

Barker, B. (n.d.). A Study of West Virginia Values and Culture.

Bauer, W. M., & Growick, B. (2003). Rehabilitation counseling in Appalachian America. Journal of Rehabilitation, 69(3), 18.

Bell, S. E., & York, R. (2010). Community Economic Identity: The Coal Industry and Ideology Construction in West Virginia. Rural Sociology, 75(1), 111–143. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1549-0831.2009.00004.x

Berridge, V. (2009). Heroin Prescription and History. New England Journal of Medicine, 361(8), 820–821. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMe0904243

Blackley, D. J., Halldin, C. N., & Laney, A. S. (2014). Resurgence of a Debilitating and Entirely Preventable Respiratory Disease among Working Coal Miners. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, 190(6), 708–709. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.201407-1286LE

Boggs, C. (2005). Big Pharma and American Medicine. New Political Science, 27(3), 407–421. https://doi.org/10.1080/07393140500226877

Burns, S. S. (2007). Bringing down the mountains: The impact of mountaintop removal surface coal mining on southern West Virginia communities, 1970-2004. West Virginia University Press. https://hdl.handle.net/2027/heb08897.0001.001

Butowsky, H. A. (1994). Rethinking Labor History: The West Virginia/Virginia Coal Mining Industry. The George Wright Forum, 11(2), 11–16.

Chisholm-Burns, M. A., Spivey, C. A., Sherwin, E., Wheeler, J., & Hohmeier, K. (2019). The opioid crisis: Origins, trends, policies, and the roles of pharmacists. American Journal of Health-System Pharmacy, 76(7), 424–435. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajhp/zxy089

Ciccarone, D. (2021). The rise of illicit fentanyls, stimulants and the fourth wave of the opioid overdose crisis. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 34(4), 344. https://doi.org/10.1097/YCO.0000000000000717

Coal, F. of. (2023, June 3). Friends of Coal | Advocate for Coal’s Essential Role in America’s Economy and Future. Friends of Coal. https://www.friendsofcoal.org/

Cognitive Development in Children | Advice for Parents. (n.d.). Retrieved December 11, 2024, from https://www.cincinnatichildrens.org/health/c/cognitive-development

Coyne, C. A., Demian-Popescu, C., & Friend, D. (2006). Social and Cultural Factors Influencing Health in Southern West Virginia: A Qualitative Study. Preventing Chronic Disease, 3(4), A124.

Derickson, A. (1983). Down Solid: The Origins and Development of the Black Lung Insurgency. Journal of Public Health Policy, 4(1), 25–44. https://doi.org/10.2307/3342183

Dyer, O. (2019). Opioid lawsuits: Sackler family and Purdue reach tentative settlement with 27 US states. BMJ : British Medical Journal (Online), 366. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.l5564

Emma, A., & Powder, D. (n.d.). What are common street names?

Eyre, E. (2020). Death in Mud Lick: A Coal Country Fight against the Drug Companies That Delivered the Opioid Epidemic. Simon and Schuster.

Finkelman, R. B., Wolfe, A., & Hendryx, M. S. (2021). The future environmental and health impacts of coal. Energy Geoscience, 2(2), 99–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engeos.2020.11.001

Fitzpatrick, L. G. (2018). Surface Coal Mining and Human Health: Evidence from West Virginia. Southern Economic Journal, 84(4), 1109–1128. https://doi.org/10.1002/soej.12260

Goldberg, T. H., & Saul, B. (2016). The aging population of the USA and West Virginia—The demographic imperative. West Virginia Medical Journal, 112(3), 32–35.

Greenlee, R., & Lantz, J. (1993). Family coping strategies and the rural Appalachian working poor. Contemporary Family Therapy, 15(2), 121–137. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00892451

Harkins, A. (2003). Hillbilly: A Cultural History of an American Icon. Oxford University Press.

hawriverfilms (Director). (2021, October 21). Mountain Top Removal [Video recording]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gKVFpa6Amug

Hendryx, M. (2015). The public health impacts of surface coal mining. The Extractive Industries and Society, 2(4), 820–826. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.exis.2015.08.006

Herzberg, D. L. (2020). White market drugs: Big pharma and the hidden history of addiction in America. The University of Chicago Press.

History. (n.d.). United Mine Workers of America. Retrieved November 15, 2024, from https://umwa.org/about/history/

Hoey, B. (2015). Capitalizing on Distinctiveness: Creating West Virginia for a “New Economy.” Journal of Appalachian Studies, 21(1), 64–85. https://doi.org/10.5406/jappastud.21.1.0064

Huang, X., Keyes, K. M., & Li, G. (2018). Increasing Prescription Opioid and Heroin Overdose Mortality in the United States, 1999-2014: An Age-Period-Cohort Analysis. American Journal of Public Health, 108(1), 131–136. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2017.304142

Jones, M. R., Viswanath, O., Peck, J., Kaye, A. D., Gill, J. S., & Simopoulos, T. T. (2018). A Brief History of the Opioid Epidemic and Strategies for Pain Medicine. Pain and Therapy, 7(1), 13–21. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40122-018-0097-6

Kerr, L. E. (1980). Black Lung. Journal of Public Health Policy, 1(1), 50–63. https://doi.org/10.2307/3342357

Kline, D., Hepler, S. A., Krawczyk, N., Rivera-Aguirre, A., Waller, L. A., & Cerdá, M. (2024). A state-level history of opioid overdose deaths in the United States: 1999-2021. PLoS ONE, 19(9), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0309938

Learning Outcomes among Students in Relation to West Virginia Coal Mining: An Environmental Riskscape Approach. (n.d.). https://doi.org/10.1089/env.2010.0001

Lewis, R. L. (1993). Appalachian Restructuring in Historical Perspective: Coal, Culture and Social Change in West Virginia. Urban Studies, 30(2), 299–308. https://doi.org/10.1080/00420989320080301

Macy, B. (2018). Dopesick: Dealers, Doctors, and the Drug Company that Addicted America (1st edition). Little, Brown and Company.

Merem, C. (2014). The Analysis of Coal Mining Impacts on West Virginia’s Environment. British Journal of Applied Science & Technology, 4(8), 1171–1197. https://doi.org/10.9734/BJAST/2014/7066

Nexus, C. (2017, January 25). What’s Driving the Decline of Coal in the United States. Climate. https://climatenexus.org/climate-issues/energy/whats-driving-the-decline-of-coal-in-the-united-states/

Ondocsin, J., Holm, N., Mars, S. G., & Ciccarone, D. (2023). The motives and methods of methamphetamine and “heroin” co-use in West Virginia. Harm Reduction Journal, 20(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12954-023-00816-8

Phillips, T. M. (2007). Influence of Appalachian Fatalism on Adolescent Identity Processes. Journal of Family and Consumer Sciences, 99(2), 11–15.

Potter, E. C., Allen, K. R., & Roberto, K. A. (2019). Agency and fatalism in older Appalachian women’s information seeking about gynecological cancer. Journal of Women & Aging, 31(3), 192–212. https://doi.org/10.1080/08952841.2018.1434951

Prater, J. B. (2006). West Virginia’s Painful Settlement: How the Oxycontin Phenomenon and Unconventional Theories of Tort Liability May Make Pharmaceutical Companies Liable for Black Markets Comment. Northwestern University Law Review, 100(3), 1409–1438.

Rabin, R. C. (2019, May 2). McKesson, Drug Distribution Giant, Settles Lawsuit Over Opioids in West Virginia. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/05/02/health/mckesson-opioids-west-virginia.html

Rice, O. K., & Brown, S. W. (1993). West Virginia: A History. University Press of Kentucky.

Saloner, B., Landis, R., Stein, B. D., & Barry, C. L. (2019). The Affordable Care Act In The Heart Of The Opioid Crisis: Evidence From West Virginia. Health Affairs, 38(4), 633–642. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2018.05049

Shapiro, H. D. (1979). Henry D. Shapiro. Appalachia on Our Mind: The Southern Mountains and Mountaineers in the American Consciousness, 1870–1920. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. 1978. Pp. xxi, 376. $16.00. The American Historical Review, 84(2), 571. https://doi.org/10.1086/ahr/84.2.571

Shriver, T. E., & Bodenhamer, A. (2018). The enduring legacy of black lung: Environmental health and contested illness in Appalachia. Sociology of Health & Illness, 40(8), 1361–1375. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9566.12777

Surber, S. J., & Simonton, D. S. (2017). Disparate impacts of coal mining and reclamation concerns for West Virginia and central Appalachia. Resources Policy, 54, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resourpol.2017.08.004

The Family That Built an Empire of Pain | The New Yorker. (n.d.). Retrieved December 13, 2024, from https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2017/10/30/the-family-that-built-an-empire-of-pain

The Last Mountain (2011). (n.d.). [Video recording]. Retrieved October 30, 2024, from https://tubitv.com/movies/312548/the-last-mountain

Thesis, A., & Laws, C. W. (n.d.). REINTEGRATION STRATEGIES TO MITIGATE CHILD ABUSE AND NEGLECT BY SUBSTANCE ABUSERS IN WEST VIRGINIA COMMUNITIES.

UNODC - Bulletin on Narcotics—1953 Issue 2—003. (n.d.). United Nations : Office on Drugs and Crime. Retrieved November 15, 2024, from //www.unodc.org/unodc/en/data-and-analysis/bulletin/bulletin_1953-01-01_2_page004.html

U.S. News & World Report. (2025, February 25). Top 10 causes of death in America. U.S. News & World Report. https://www.usnews.com/news/healthiest-communities/slideshows/top-10-causes-of-death-in-america

Very Ape (Director). (2017, May 30). Oxyana (Documentary) [Video recording]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=X5xAu1csU_c

Warfield, S., Pollini, R., Stokes, C. M., & Bossarte, R. (2019). Opioid-Related Outcomes in West Virginia, 2008–2016. American Journal of Public Health, 109(2), 303–305. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2018.304845

Wheeler, H. N. (1976). Mountaineer Mine Wars: An Analysis of the West Virginia Mine Wars of 1912-1913 and 1920-1921. The Business History Review, 50(1), 69–91. https://doi.org/10.2307/3113575

Winterhalter, E. (2021, February 3). The Tragedy at Buffalo Creek. JSTOR Daily. https://daily.jstor.org/the-tragedy-at-buffalo-creek/

WVGES Geology: History of West Virginia Coal Industry. (n.d.). Retrieved October 19, 2024, from https://www.wvgs.wvnet.edu/www/geology/geoldvco.htm

Zezima, K., & Higham, S. (2018, April 12). Drug executives to testify before Congress about their role in U.S. opioid crisis: Five drug distributors will be questioned about how millions of pills flowed to West Virginia. The Washington Post (Online); WP Company LLC d/b/a The Washington Post. https://www.proquest.com/docview/2024337491/citation/A089727376B14460PQ/1