A Generational Pattern of Corporate Abuse, Dependency & Neglect in West Virginia: From My Family’s Perspective

By Norah Hively

Since the 19th century, West Virginians have been victim to the corporations that exploit them. The coal industry created a dependency, allowing consistent disregard for basic human rights in their practices out of hunger for money and power.

People in poverty had no choice but to endure the obstacles they faced. No choice but to endure the exhaustion, injury and pain that came with a life dependent on the companies that exploited them. “What else can you do? You have a family to provide for. You really have no choice,” says my great-aunt Darla whose father, my great-grandfather, was a coal miner. The injuries, disease and job loss caused by a reliance on the coal industry, allowed drug companies to prey on the vulnerable– birthing an opioid epidemic in West Virginia.

Effects of dependency and corporate abuse, fundamentals originally instilled by coal companies, allowed for drug companies to take over after coal’s decline. When asking my uncle Tommy how he has seen his once thriving coal community completely change, he plainly states: “Drugs.” Modern-day West Virginia continues to struggle after the height of a state-wide drug addiction. I spoke to both sides of my family about what they, and West Virginians alike, have gone through in the aftermath. “I don’t think we’re as bad off as what we were,” says my cousin Mary in reference to West Virginia and its opioid epidemic. “But, we still have a long way to go, just as the rest of the country does. You need to open your eyes and see what’s going on. Don’t sugarcoat it.”

How We Got Here: A History of Abuse & Dependency

In search of an opportunity far from his homeland my great-grandfather, Savino Chiericozzi, boarded a ship to America at the age of 16. He left his small Italian village of Ascoli Satriano in the wake forever. As my mother’s side of the family has told me, on April 11, 1909, he arrived at Ellis Island in New York City. There he spent some time laying bricks, laying the foundation of one of America’s greatest cities.

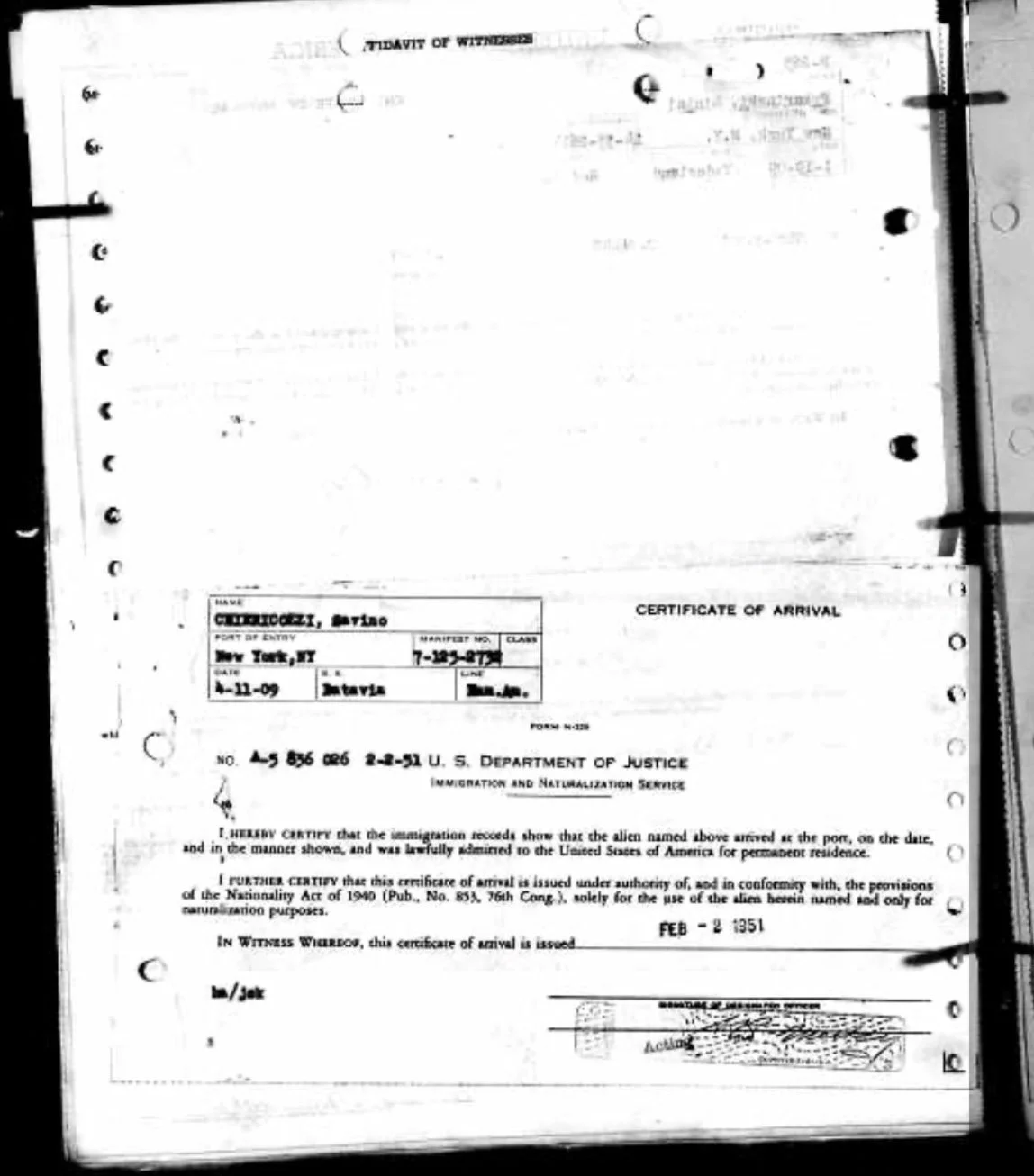

The certificate handed to my great grandfather, Savino Chiericozzi, on April 11, 1909. Scan of certificate provided by Pete Chiericozzi, Savino’s son and my grandfather.

Not long after arriving in the United States, Savino found the chance he’d been searching for when a friend told him about a job in West Virginia. It would provide housing and a steady income. My great-grandfather, an immigrant who came to America with nothing, in search of a living outside of the economic treachery he faced in his home country, hopped on the opportunity as fast as he hopped on a train to the Appalachian Mountains. It was there he began his career as a coal miner. In 1931, Savino married my great-grandma, Victoria Girardi. Rosario Girardi, Victoria’s father, was also an Italian immigrant who found a job working in the coal mines. Together, Savino and Victoria settled down, raising five children on a coal camp in Maitland, WV.

Family portrait of my great grandparents, Savino and Victoria Chiericozzi, and my great aunts Rosie and Sissy before their three brothers were born. Photo provided by Rosie Hurt.

Just like on my mother’s side, my father’s side of the family also held careers in the mines. My ancestors' occupation in West Virginia goes back much further, with my grandmother’s side residing in the U.S. since the Mayflower. My uncle was a coal miner. His father, my grandfather, was a coal miner. My great-grandfather was a coal miner and so was his father. Generations have gone by as the West Virginia coal industry was created, molded, thrived and crashed–and my family experienced it all.

From the beginning, the coal industry provided housing and mining careers for poor Americans in the southern Appalachians. However, with an awareness of miners’ reliance on their jobs, coal companies were able to get away with malpractices such as decreasing wages and neglecting to regulate safety in the mines.

Negligence and abusive practices by the coal companies caused their miners to meet in secret. These groups were called ‘unions.’ Unions organized to express concerns about their working conditions among fellow miners. In 1890, soon after mining began in the U.S., the first official union chapter was established by the United Mine Workers of America (UMWA).

For many years, unions were seen by coal companies as a threat. Famously known as “The Mine Wars,” taking place at Cabin Creek and Paint Creek from 1912 to 1913 as well as in Logan and Mingo Counties from 1920 to 1921, the protests were a result of unions banding together to create change. From these instances were prolonged strikes resulting from coal companies refusing to meet miners’ demands for better working conditions. After a long back-and-forth, in both cases, of violence between miners and their coal companies, some of the miners’ demands were met to some degree and unions were able to organize openly. From then on, it was unions, groups of miners, that created regulations for mines. Union men met with coal companies to discuss concerns with working conditions and to put policies in place.

My great-aunt Darla Toler’s father and my great-grandfather, Buford France, who I called “Papaw Buford,” was a union man like most miners in my family. He worked in the mines for 42 years and served the UMWA for 72. “He was chairman of the committees. And they would go head to head with the coal companies about safety and everything,” says Darla. “Then, a lot of times, they would strike. The men would take their grievances and go to Daddy and he would have to kind of mediate.”

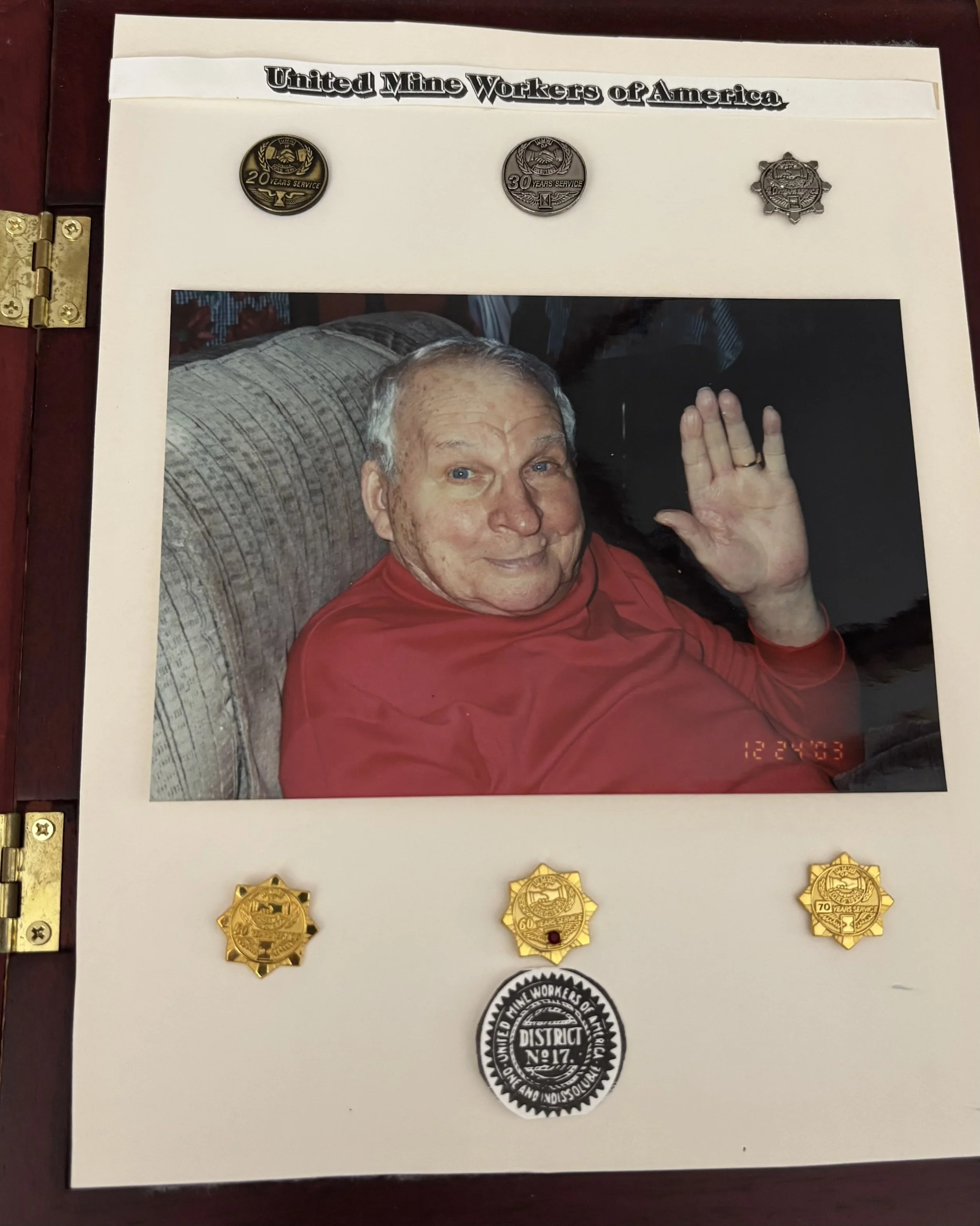

A framed display of her father, my Papaw Buford, doing his classic wave at the camera snapping a photo, sits in my great aunt Darla’s home on January 4, 2025. Surrounding him are UMWA pins representing his years serving the union. Photo by Norah Hively.

Strikes didn’t end after the infamous Mine Wars. Coal companies continued to neglect the best interests of their miners. “They would strike for better working conditions, better benefits and safety standards,” says my uncle, Thomas “Tommy” Hively II, 62, a third and fifth-generation coal miner on each side of my father’s family. “When my Grandpa Holbrook and my Papaw, dad’s dad, used to work in the mines, they worked 10, 12 hours a day. The union negotiated eight-hour days.” For all of West Virginia's mining history, unions had the responsibility of creating change for themselves and other miners when corporations continuously turned a blind eye.

The mines were never a safe place to work. Despite more safety regulation by union efforts, injury still persisted. Both Papaw Buford and Savino, my great-grandfathers on my father and mother’s side, were injured working in the mines. Papaw Buford broke three toes in a slate fall. Savino’s injury was severe. “He [Savino] was coming out of the mines and there was a small coal carrier. So, he hopped on that to get where the lift was to take him up to ground level. And, somehow, someway he fell. And it severed–ran over–his left arm,” says my grandfather Pete “Papa” Chiericozzi, 82, Savino’s son.

My grandfather, Pete “Papa” Chiericozzi, with his childhood friend from the coal camp standing in front of Kopper’s Company Store in Maitland, WV. Photo provided by Pete Chiericozzi.

Koppers Coal Company, who my great-grandfather worked under for over 20 years, according to Papa, paid his hospital bills following the accident. However, they refused to provide Savino with any further compensation for the injury, arguing it was my great-grandfather's fault since he was helping someone out in a place he shouldn’t have been. Without Savino’s arm, now chopped off four inches from his elbow, he would have to go unemployed, leaving him and his wife Victoria to look for their next options.

“They talked about getting him an attorney because they weren’t gonna offer him anything. And, they were told that if you do that, you’ll never work in the coal mines again,” says Papa. “And that scared him so much that they did not pursue any kind of attorney action.”

The mines were the Chiericozzis’ livelihood. Not only was it Savino’s career, but they also lived in company housing and bought goods on company credit. That would mean risking everything they had. Jeopardizing his return to the mines was not an option–and the coal company knew it.

Eventually, Savino went back to work in the mines. He was given a hook attachment for his arm. However, the mines weren’t done taking a toll on his body. Savino, like many miners, was diagnosed with Black Lung - just one of many casualties in my family’s history related to corporate dependency and poor health outcomes.

According to West Virginia University Professor Emeritus Michael McCawley, Ph.D, coal worker’s pneumoconiosis (CWP), also known as “black lung disease,” is caused by the inhalation of silica– a type of dust particle caused by the drilling of rock. The disease comes with a long history of avoidance. Dr. McCawley says black lung's acceptance in American mining history–along with a push for preventative measures against the disease– was always followed by tragedy.

“The history of black lung was basically the history of coal mining regulations,” explains Dr. McCawley. “The coal miners and the regulators will tell you the same thing: coal mining regulations are written in the blood of miners.”

The blood of these miners includes my family. Savino, my great-grandfather on my mother’s side, never received compensation for having the disease. He died of heart complications that were worsened by his having CWP. On my father’s side of the family, my great-grandfather Robert Edward Hively Sr., died from the disease. However, Papaw Buford, my other great-grandfather on his side, was able to receive compensation–eventually.

“He had to have a doctor verify he had black lung. Then, the doctor would apply for the patient and go through that process,” says my great aunt Darla, Papaw Buford’s daughter. “And, it may take two or three sessions before they were finally approved.” This process took years. It was physical after physical. My great-grandfather was required to have a lawyer, who he would have to pay, taking 30 to 50% of the settlement, according to Darla. But, regardless of the stress and strife of getting approved, her father needed the money.

Money was tight after Papaw Buford retired when he was 57, but the Black Lung compensation helped. He had been working as a miner since he was 15 years old after his father, Ogle Marion France, died at 42. Working 12 to 16 hours a day in the mines had taken a toll on my great-great-grandfather. “Back in them days, after the husband died, his widow had 30 days from the day they buried him to either, a) marry a miner who worked for the other company, or b) their oldest son went to work in the mines, because they lived in company housing,” says my uncle Tommy. “Or else they put them out.”

My great-great-grandfather, Ogle Marion France (left), operating a coal car in the West Virginia mountains. Photo provided by my great-aunt Melanie.

Ultimatums such as these were a norm for coal corporations. Even as their workers faced injury, disease and death, they rarely showed remorse. Regulations were never made until they were forced. “Whenever there is a tragedy of some sort with a coal mine, that’s what they see it taking to make those changes in the law,” says Dr. McCawley. “There has to be an enormous tragedy that gets the public's attention before the government at least feels the push to make a change. Because, most of the time, those changes are resisted strongly by the industry.”

Papaw Buford is held by his grandfather, my great-great-great-grandfather, Edward Monroe France, who took care of the mules that pulled coal cars in and out of West Virginia mines. Photo provided by my great-aunt Melanie, Papaw Buford’s daughter.

Throughout coal mining history, the industry exemplified little concern for its workers, but miners endangered their well-being working for these corporations because they had to survive. In order to make a life for themselves, it was virtually the only recourse in West Virginia. Coal was the economy, that is until it wasn’t.

On Thanksgiving day of 1953, my great-grandparents, Savino and Victoria, told their children the mines surrounding Welch, WV, including Maitland’s, were closing. It remains a core memory for both Papa and his sister, my great-aunt Rosie, 88. Before that moment, coal camp life was all they knew. Now, life as they knew it would vanish. “I tell you about Welch, when the mines were operating, it was like New York City. You could not get in or out of Welch because of the traffic,” says Aunt Rosie. “Cars were lined up for miles wherever there was a coal camp and people were coming to town to spend their money. It was rich. It was rich.”

After the mines closed, everything in Welch started to close. There was nothing left. No industry, no jobs. People still reside in Welch, but the hustle and bustle has long since vanished and the resemblance of a ghost town remains. In my great-grandmother Victoria’s hometown of Williamson, the same thing happened. The coal town diminished. Reliable jobs and opportunities disappeared.

Today, in both Welch and Williamson, abandoned buildings– once shops, businesses, shops and schools– still stand decaying. In Welch, even the town Walmart recently shut down. On the southern border, in the depths of the valley, the air is silent and thick with a forgotten past.

In other areas of West Virginia, coal’s economic stability fluctuated over the years. “The coal mines go in boom and bust cycles. Every five to 10 years, it goes from boom to bust,” says my uncle Tommy, a retired coal miner. “That’s just the way it is. It depends on the steel market.” When the U.S. turned to cheaper, foreign steel, domestic coal mines closed. Producing steel requires coal so when the steel industry is down, so are the coal mines.

Uncle Tommy has lived in Chesapeake, WV, a small coal town nestled in the Kanawha Valley, his whole life– witnessing the coal industry’s highs and lows first-hand. According to my uncle, Chesapeake was incorporated in 1948. My father, Brett Hively, 52, and my uncle Tommy’s hometown reached its economic prime in the 60s and 70s. However, as Uncle Tommy experienced, the coal industry saw a decline in the next decade. In 1987, he was laid off. “The 80s was a bad time, a lot of the steel mills closed down,” says Uncle Tommy. “In the 80s and early 90s, things were hard here. There wasn’t any jobs around.”

As the job market declined statewide, a new industry found its way in–the pharmaceutical industry. First, Big Pharma targeted the long-since-forgotten rural mountain towns. In the 1990s, towns in McDowell County, like Welch and Williamson, along with those in Mingo County, became the hotspots where opioid pills came flooding into the state. Pills were shipped to small pharmacies on the southern border of West Virginia, fulfilling prescriptions from doctors who were later convicted of federal crimes. People caught on, traveling from other parts of the state to obtain an easy prescription. The drugs reached more central places like Chesapeake when people began selling pills on the streets for money. “When people are poor, they’re renting a house, they don’t have a job and they’re getting food stamps and welfare,” says Uncle Tommy. “People started to look to selling pills to make money off their prescriptions.”

Soon the entire state was consumed. Big drug manufacturers and distributors created a new kind of dependency after the decline of coal. Through corporations pushing pills into West Virginia, an opioid crisis was born - not just for the region, but for my family too.

The Opioid Epidemic in West Virginia

Fresh out of graduating high school my cousin, Eric Stanley, 6’3”, big-build, brown hair with hazel eyes, knew exactly what he wanted to do: play college football at Marshall University in Huntington, WV–his hometown. Eric was the captain of the football team in his senior year. His passion for the game never ceased. Even when he started having back problems his junior year, he continued to play. Eric attended Marshall and was given the opportunity to walk on to the football team his freshman year of college. He started to see Marshall’s football team physician as his primary care doctor.

Grandma and grandson, Aunt Rosie and Eric, wearing Marshall green while posing on Great-Aunt Rosie’s couch in Huntington, WV. Photo provided by Eric’s family.

Soon after Eric walked onto the team, his physician got real with him. He told Eric he could not continue to play football with his back in its current condition. He recommended getting surgery and coming back next season.

“It devastated him,” says my cousin, Mary Stanley, 62, Eric’s mother. “ He came out and when he got in the car he immediately started crying.” After that day, Mary recalls that everything began to change. Eric started drinking beer when he never had before. He began to abuse the pain medication prescribed for his back. Once he couldn’t get that anymore, he started to look for it in other places. “And that became his life,” says Mary. “It was drinking and the next thing I know it was snorting drugs.”

Huntington, WV

Tori Stanley, 32, Mary’s second child and Eric’s sister, recalls beginning to use drugs in high school. “It started with me, of course, smoking weed,” says Tori. “And then that turned into ‘Oh well I have prescription pills.’ Well then, of course, you try that too.” Eric and Tori recreationally took pain pills together. Later on, Tori went further than her brother, abusing heroin, meth and fentanyl as well. “It just went from one thing to the next thing, to the worst thing, to the worst thing,” says Tori. “And just because it’s so available here, it really snowballed for me.”

Here, for Tori, is Huntington, West Virginia. Huntington, bleak and industrial, was a hub for overdoses within the state of West Virginia during the peak of the ‘third wave’ spike in the opioid epidemic.

Spike in Numbers

In their study, “A state-level history of opioid overdose deaths in the United States: 1999-2021,” researcher David Kline and other contributors, describe a three-wave spike in opioid deaths by individually observing states’ death tolls between the years 1999 and 2021. The three waves present as: a spike in prescription drug-related deaths from 1999-2005; a spike in heroin-related deaths from 2010-2014; and a spike in synthetic-related deaths from 2014-2021. Dr. Kline’s data finds West Virginia to be a clear outlier for prescription opioid-related deaths. West Virginia had more than twice the amount of any other state– spreading to my family members and citizens alike. Opioid prescription deaths skyrocketed in 1999 and continue to increase along with heroin and synthetic opioid-related deaths. My cousin Tori saw this spike firsthand, being addicted to heroin and fentanyl herself.

One night in 2015, early in the third wave spike, Eric received a text from Tori’s recent ex-boyfriend at the time and father of her first child. He said to come over because he had pills for them to get high. “I saw the text messages on his phone,” says Mary. “Eric said ‘No, I don’t have any money, I don’t want to come over there.’ Christian’s father responded ‘You don’t have to pay me right now, come on.’ And he let himself be talked into it.” That night, Eric and Tori’s ex-boyfriend each snorted a pill typically used to treat cancer pain patients called Opana ER, also known as Oxymorphone. Eric took one half there, snorting the other half when he arrived home that night.

“He had just had surgery on his meniscus and he hadn’t had drugs or beer or anything for like three weeks,” says Eric’s mother, Mary. “Then, boom, right off of the bat, he went a little overboard and his system, his heart, couldn't stand it.”

Eric wears his Cincinnati Reds shirt at my great aunt Rosie’s table, at her home in Huntington, WV. He prepares to blow out the candles on the cake she baked to celebrate another birthday on March 24, 2014, a year before his passing. Photo provided by Eric’s family.

On the morning of March 9, 2015, Eric Stanley was found dead by his mother in his basement bedroom of their family home. He was 23 years old– another casualty of the prolonged historic effects of a dependency caused by abusive corporations showing no care for the people whose lives they ruined.

State of Emergency

“Once my brother passed away, the EMS told us that they literally had to leave our house to go to respond to another overdose,” says Tori. “And that’s when it became really real to me as to how many people were passing away. And that’s when it really became an emergency here.”

In August 2016, over a year after Eric’s death, Mary says that Huntington, WV, saw 26 overdoses in one day. In the small city of Huntington with a population of 47,725 (United States Census Bureau, 2016), there were not enough ambulances to efficiently respond to every overdose. None of the patients were referred to any recovery services. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control (CDC) reports that, in October of 2016, after days like the one in Huntington persisted state-wide, the West Virginia Bureau of Public Health (BPH) released a public health advisory.

“It started a long time ago, before Eric,” says Mary. “It just didn’t start getting bad until Eric. I noticed all these kids dying of overdoses.” The public health disaster in Huntington is not simply a result of all the citizens deciding to abuse their medication. The story begins further back. It runs much deeper.

Who Started It

An epidemic rooted in greed is what characterizes modern-day West Virginia’s struggle with addiction. Greed drove pharmaceutical manufacturing company, Purdue Pharma L.P., to put a drug stronger than morphine on the market. In 1987, OxyContin, or oxycodone hydrochloride controlled-release tablets, was born: its invention initializing chaos that would later consume millions of lives.

“Purdue Pharma aggressively marketed OxyContin as less addictive than other opioids, claiming a lower risk of dependence due to its extended-release formulation,” says Nandini Manne, Ph.D. in Biomedical Sciences at Marshall University. “This led to widespread prescription of opioids leading to dependence and misuse.” Dependence on OxyContin spread like fire when it entered the market– starting with rural mountain towns on the southern border of West Virginia, then extending to cities like Huntington, Charleston and Princeton. Citizens’ addiction to opioid pills was followed by increased use of stronger recreational drugs such as heroin and fentanyl.

According to Dr Manne, when evidence of widespread misuse arose, Purdue emphasized “patient accountability and personal responsibility.” Through these deadly business strategies, the Sackler family manipulated doctors and patients across the country by ignoring the realities of OxyContin and capitalizing on its addictive qualities.

“Victim blaming significantly harms those trying to recover by instilling deep feelings of shame, guilt, and self-blame,” says Dr. Manne. “This internalized stigma undermines self-esteem, increases mental health issues like depression and anxiety, and discourages individuals from seeking necessary treatment.”

For decades, victim blaming has commonly been used to dismiss the struggles of addicts. “Historically, society has framed addiction negatively, notably through policies like the War on Drugs, which criminalized individuals and reinforced victim-blaming narratives,” says Dr. Manne. “This punitive approach contributed to widespread stigma, leading to labels such as ‘junkie’ or ‘addict’ that dehumanize and marginalize individuals struggling with substance use.”

Being a recovered addict herself, my cousin Tori is aware of how others view addicts in such a negative light. “I do have a soft spot for people who are still in addiction just because I know how hard it is to try to get out of something like that,” she says.

Widest Possible Audience

Tori’s relationship with drugs only worsened after the death of her brother. She was less than two years younger than Eric. She always looked up to him and wanted to be with him all the time, even hanging out with him and his friends whenever she could. “He was more of a best friend than anything. He was everything a brother should be,” says Tori. “He stood up for me. He was always someone I could call on if I ever needed anything.”

Eric poses with our cousins, Maria and Alexandra, in 2014. Photo provided by Eric’s family.

Losing her brother and best friend was one thing, but Tori emphasizes the pain of seeing her parents lose a child to overdose was the worst part of it all. Today, overdose is the leading cause of death for Americans ages 18-44, according to the Centers for Disease Control (CDC). However, statistics show opioid addiction reaches people of all ages in West Virginia, even children. In a 2019 study funded by the United Hospital Fund titled: “The Ripple Effect: National and State Estimates of the U.S. Opioid Epidemic’s Impact on Children,” West Virginia is number one overall as the state with the highest number of children affected by Opioid Use Disorder (OUD) at a rate of 54 per 1,000 children. This number includes cases of accidental ingestion of opioids and children or their parents having OUD.

Tori’s children were among these numbers. Her addiction became so bad that she gave up custody of both her kids, handing them over to her parents. Addiction took hold of everything she was and everything she once had. “It’s the devil really,” says Tori. “It’s like you’re living in hell and you can’t get out.”

Even though Tori had her kids taken from her, she remembers the haze of not understanding the misery she was in. “I was so numb at the time to everything that was going on,” says Tori. “I mean, of course I cared about my children, but I cared about getting high a lot more.” Still consumed in the tumult of her addiction, Tori would wake up in the middle of the night, thinking about how she had lost everything–her kids, her family, her life. But, for a temporary fix, she would get high again, trying not to think about what she had done.

Target Market

Tori experienced the hold opioids had on Huntington, WV, firsthand. “I used drugs with people who were probation officers and people who were models of the community. There was no respect for which person. There were homeless people that were abusing drugs, but there was also regular people in this community that were abusing drugs as well,” says my cousin.

According to Dr. Manne, the state's heavy dependence on coal mining, manufacturing, and labor-intensive jobs resulted in more work-related injuries and chronic pain, thus creating a higher demand for pain medication. “This vulnerability was compounded by frequent job instability, widespread poverty, unemployment, aggressive pharmaceutical marketing, and inadequate regulatory oversight in prescription practices and drug distribution—all contributed significantly to West Virginia’s opioid epidemic,” says Dr. Manne. Higher accessibility to pain pills spread to other demographics within the state, allowing the effects to reach all populations. No one could escape the results of corporate greed and neglect.

“It just devastated this town, again,” says Mary, Tori’s mom. “Seems like Huntington’s always in it. We might have something good happen, then the next thing you know we go through this long stretch where it’s nothing but bad.”

Burial site for some members of the tragic plane crash that killed the 1970 Marshall Football Team. The grave sits layered in white at Woodmere Memorial Park in Huntington, WV, on January 7, 2025. Photo by Norah Hively.

Just like the rural mountain towns in McDowell and Mingo counties, the city of Huntington became consumed with addiction. Its citizens became dependent on Big Pharma’s pain pills. The community witnessed overdose after overdose. One afternoon in August 2018, a couple of years after Eric’s death, was no exception. Mary was in her home when she noticed an unfamiliar car parked in the driveway. A man sat slumped over in the vehicle.

Wayne Stanley, 62, Mary’s husband, went outside to check on the man in the vehicle. He was overdosing. Wayne started giving him chest compressions, and when that didn’t work, he gave him a dosage of Narcan, also known as naloxone.

“Naloxone is a drug used to reverse opioid overdoses,” says Dr. Manne. According to the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), Narcan can either be used as a nasal spray or injected into the muscle, veins or under the skin. It then attaches to opioid receptors to block or reverse the effects of opioids from continuing. Because of the frequency of overdoses in Huntington and their own childrens’ experiences with opioids, Mary and Wayne Stanley kept Narcan handy at their home.

Wayne gave the man a dose of Narcan, running back into the house to grab him a second dose when he didn’t react. Wayne, a nurse, was able to save the stranger’s life. He woke up unaware of what had happened.

“My neighbor, he was a retired sheriff’s deputy, goes, ‘You talk about hero, Wayne was my hero,’ because he was outside watching the whole thing,” my cousin Mary explains. “I said ‘Yeah, he’s a hero. Too bad we couldn’t do it for our own child, but we did it for somebody else’s.’”

Kanawha City, WV

Like Huntington, the capital city of Charleston and the surrounding towns, have faced overwhelming tragedy since the opioid epidemic arrived in the U.S. Kanawha City is one of those suffering towns. Kanawha City, WV, a once thriving town, with businesses and shops all down the main road, sits grey and rundown.

For over forty years, Darla and Donnie Toler, my great aunt and uncle on my father’s side, have lived in their house across the street from Kanawha City’s now abandoned KMart. Their split-level home, which is distinguished by its spacious front window, is the same house where they raised their children, Lee and Alisha Toler. It’s the same house they ended up raising their grandchildren as well.

Attempting to Reverse the Damage

Darla, 77, and Donnie, 78, were not expecting to raise children at their age. Donnie, a retired mining machinery salesman, had been devoting his time to being a preacher who builds strong bonds with his congregation. He and Darla went to visit one of their parishioners in the hospital one afternoon. To their surprise, they saw their daughter, my cousin Alisha Toler. “She was over in the next room with her boyfriend then and she had an ultrasound picture,” says Darla. “And I just about fainted.”

By this time, Alisha had been struggling with drug addiction for years. Darla and Donnie hadn’t seen their daughter in months. They had no idea of her whereabouts after having her move out of Donnie’s parents’ house which he inherited. It was a failed attempt for Alisha to get her act together.

Now, they stood, horrified at the idea that their daughter, who could barely take care of herself, was pregnant. “I said, ‘Of all things that you need in your life, bringing a child into this world is not one of them. How are you going to care for it? Provide for it?’” Donnie recalls the first thing he said to her. Then they found out Alisha was pregnant with twins, doubling her parents’ worry.

Growing up, Alisha was your normal, spoiled daddy’s girl, as described by her parents. “She was a good student, never had to worry about her in her classes. She was a flag girl in junior high,” says Darla. “She was just your typical teenager.”

Alisha’s father, my great uncle Donnie, suspected that she had been smoking marijuana in high school. He recalls seeing signs Alisha was heading towards a rocky path. But, it wasn’t until after high school that Alisha’s parents realized she had an issue with substance abuse.

My cousin Alisha struggled with Substance Use Disorder (SUD). According to Dr. Manne, SUD involves one’s inability to control their use of substances. “One of the common misconceptions is that addiction is a moral failing or just a lack of willpower,” says Dr. Manne. “However, it is a chronic mental health disorder that needs to be treated.”

Before graduating high school, Alisha had secured a job at Charleston Area Medical Center (CAMC) Memorial Hospital. “She was top of the class and got a real good job at Memorial,” says Darla. “But she didn’t stick with it.”

“Another misconception is that it affects only ‘certain groups of individuals.’ The fact is that irrespective of race, sex, age, ethnicity, socio-economic status,” says Dr. Manne. “SUD affects everyone equally.”

Darla and Donnie persistently did everything they could to try to help their daughter. Psychiatrists, doctors, counselors and rehabilitation programs. They also tried treatment with Suboxone which, according to the American Addiction Centers (AAC), is a combination drug consisting of buprenorphine and naloxone, that can help lessen opioid cravings and withdrawal side effects in addicts. “It has a high affinity for opioid receptors (mu) and dissociates from them slowly,” says Dr. Manne. “This results in milder and less/weaker withdrawal symptoms for the individual.”

Alisha’s parents invested so much of what they had to try to help her get clean. “[Alisha would say] ‘I promise, I promise I want to get off of this. I want to get away from this, I promise,’” says Darla. “We wanted to believe it. And, I think she meant it, but she just couldn’t break away.”

Child Neglect

Alisha gave birth to a boy and a girl, Layne and Layla, on August 22, 2013. Both babies had health complications—Layne suffered the most. He was in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU) for a couple weeks as a result of opioid withdrawal symptoms and underdeveloped lungs. The twins were both born with weakened eyesight, wearing glasses from an early age.

Despite their birth defects, Layne and Layla lived and remained in the custody of their biological mother and father. “It was a volatile relationship. He drank. She drank. He used drugs. She used drugs. They would fight and carry on. The police was there at the house there in Chesapeake all the time,” says Alisha’s father Donnie.

Alisha and her boyfriend, Layne and Layla’s biological father, butted heads with the police often. The couple would fight constantly. Her boyfriend was taken to the police station regularly. Every time something like this would happen Child Protective Services (CPS) would call Darla and Donnie asking them to take the kids.

“We’d keep them for a month and they’d say ‘Well, we’re going to see if we can take them back up there for a day.’ Then they’d take them for a day. Then they’d bring them back. Then they’d come back and do it the next week. Then they’d do that for two or three more weeks,” says Donnie.

After that, CPS let them stay overnight and, if that went well, they would take them back to stay the weekend. Then CPS would let them stay a week, and, if the week went well, they would let them stay for good until the next fight broke out. “CPS would call at two or three o’clock in the morning saying ‘Can we bring the kids down there? Can you come and get the kids?’ ‘Yeah,’” says Donnie discouragingly. Donnie and Darla went through this full process with CPS, passing the children back-and-forth, four times.

Tim Bradford, a family court lawyer in West Virginia, has seen the amount of cases involving opioids increase drastically. He recalls seeing the movie Trainspotting (1996), and thinking that would never happen in West Virginia. “When I was a public defender, and that was from 1994 to 98, I don’t think we had more than two heroin cases in the office,” says Bradford. “And, within a decade, it was worse here than it probably ever was in Scotland.”

Just the fact that Bradford was even seeing these cases gave rise for concern. When so many abuse and neglect cases involving a parent using drugs came flooding in, they had to be dealt with and the state wasn’t prepared. “The downside with keeping these cases confidential is, when a case is handled poorly, no one knows it. There’s no public oversight,” says Bradford. “And they have so many of those cases, there’s no way they can really pay attention to them.”

Layne and Layla’s parents were arrested for child neglect multiple times. “I’d come by just to check on them. I’d go in. Alisha would be in bed passed out on drugs and the kids would be trying to find something to eat,” says Donnie. “Eggs all over the kitchen floor. Flour all over the house. They’re in the bathroom playing in the bathtub. Just two or three years old.”

Darla and Donnie would arrive at their daughter’s house with the door wide open, people they didn’t even know coming in and out. There seemed to be little care for the twins’ well-being. “Layla, one time, had a big place on her head and they had let her fall out on the porch or something,” says Donnie. “And then, Layne, one time, had a big old place on his foot. They had taken the lid off of a grill or something and laid it down and he had stepped on it.”

Foster Care in West Virginia

It took a while before Layne and Layla’s grandparents were able to have a shot at adopting them. “The state of West Virginia does everything they possibly can to keep these kids with their biological parents,” says Uncle Donnie. “And they will typically not allow anyone older than 50 to adopt a child. And we were well out of that age range.” But, since Donnie and Darla were the twins’ grandparents, they made an exception. “We went through foster parenting training, first aid classes, all that stuff just to keep the kids,” Donnie says. “Because the state had custody of them we had to go through that to keep them. Then, to adopt them, we had to go through this process with lawyers to get the adoption.”

In 2017, when Donnie and Darla were granted custody of Layne and Layla, there were over 7,000 children in foster care in West Virginia alone, according to the United States Health and Human Services (HHS). “They were sending them [children] to other states to help because they had so many of them,” says Donnie. “That was when the drug, oxycodone, was so widespread.”

Alisha Toler died on March 5, 2022, as a result of an accidental fentanyl overdose. She had taken a pain pill not realizing it was laced. She was 41 years old.

“We didn’t know it for a week– that she was dead,” says Donnie. He had received a call from Walker Machinery, where Donnie used to work, with the employee saying the police had been trying to reach him.

“And I said ‘For what?’ and he said, ‘Well, they just need to talk to you.’ And I said, ‘For what?!’ And he said, ‘Well, your daughter is dead.’ And that’s how we found out.”

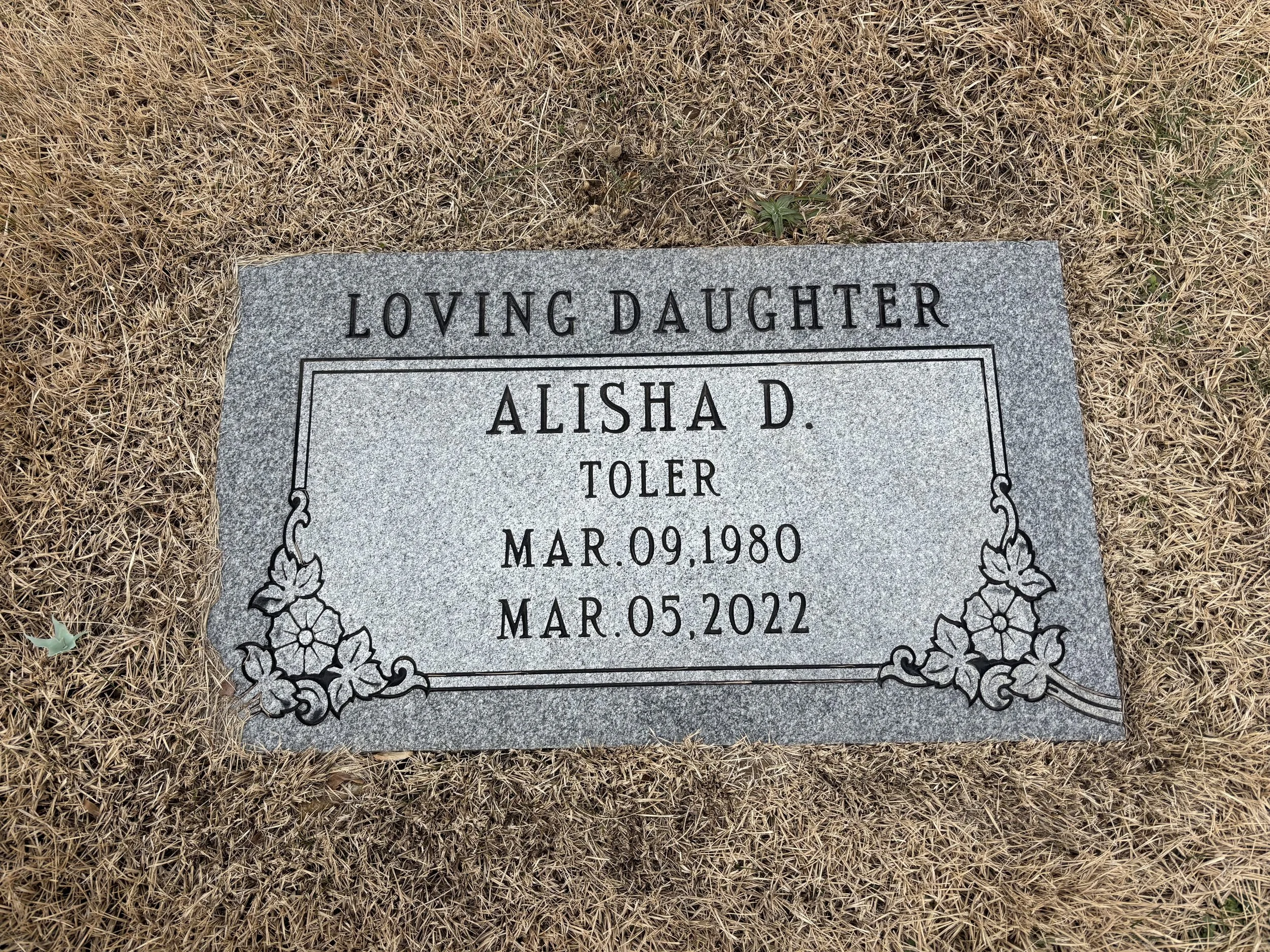

My cousin Alisha’s foot stone embedded in the grounds of Montgomery Memorial Park in Hugheston, WV, where dozens of my family members rest. Photo taken by Norah Hively on January 5, 2025.

The pharmaceutical industry, through their selling of pain pills to West Virginia in alarming numbers, was able to completely sever the relationship between a daughter and her parents– to the point where they had no awareness of her death. Layne and Layla would never get the chance to know their biological mother when she was free from addiction. The drugs had completely consumed her.

A month after Alisha’s death, Donnie and Darla Toler came dangerously close to losing their other child, Lee Toler, 49, to a heart attack. Miraculously, Alisha’s brother Lee survived his heart surgery, but the pain from what he and his family had been through, as a result of an addiction fed by Big Pharma, still lingered. “We went through a nightmare we really did,” says Darla.

Chesapeake, WV

Eight miles south of Kanawha City is a small coal town called Chesapeake, WV. You can drive through the whole town in less than four minutes. One road shoots straight through. Houses, churches and coal mounds line either side of the street. Chesapeake, nestled in the Kanawha Valley, is sandwiched between the Kanawha River on one side, and railroads then the interstate on the other. Like most coal towns, it is small and cramped. In such close quarters, everyone knows everyone. Or at least that’s how it was when my dad grew up there.

“It [Chesapeake] was nice. Back in the late 70s and early 80s. Everybody was working. The environment was thriving so far as jobs go,” says my father, Brett Hively. “It was nice then. Now it’s a shit show.”

My father is the middle child of three boys in his family. His older brother, my uncle Tommy, who has lived in Chesapeake his whole life, agrees with his brother when he says the town has become rundown since their childhood. They both agree this is a result of drugs taking hold of their community–taking hold of their youngest brother, Matthew.

Learning About Addiction the Hard Way

Morrigan Hively, 27, spent her early childhood years living in West Virginia before she moved to North Carolina with her mother in 2002. Morrigan and I were the closest pair of first cousins growing up, despite our age gap. We spent hours playing with dolls and creating made-up worlds only we knew about. But, even with all our whimsical laughter and fun, I always noticed her immediate family dynamic was much different than mine.

A photo from my mother’s photo album of Morrigan and I, in 2005, playing “tea party.” At our grandparents’ house in Chesapeake, WV, we filled our cups of ‘tea’ with water, imagining ourselves as princesses in a castle.

Morrigan’s father is my uncle, Matthew “Matt” Hively, 49. Morrigan’s mother was his first of three wives. Morrigan’s relationship with her father has been strained for as long as she can remember. Weekends assigned to her father would often be spent two doors down at our Mamaw and Papaw’s house. Even so, there were still many times she had to endure going to Matt’s house, because of his shared custody over her.

Morrigan could always tell there was something wrong when she’d go over to her father’s house. For a long time, she didn’t know why he’d become so forgetful, agitated and scary. “That was really hard, like, not knowing what it was but knowing something was going on,” Morrigan says.

As a child, Morrigan recalls a drawer in the house that always had needles in it. She remembers pills being scattered around the house. She could always tell when Matt was about to go out of consciousness. Countless times Matt came close to starting fires from knocking out with lit cigarettes in his hands. Little Morrigan, or “Mo” as my family called her, would have to pry cigarettes loose from his pale fingers.

Morrigan finally pinpointed where Matt’s odd behavior was coming from on her tenth or eleventh birthday. “I had called him for his birthday and…no, actually, I had called him for my birthday. And he didn’t know who I was, he didn’t know why I called,” says Morrigan. “He was completely out of it, I had to hang up the phone. And I was like ‘Oh, this is what drug use is.’”

Chronic Pain Management

My dad can’t fully pinpoint how his brother Matt's addiction progressed. “I think more than anything it was the company he kept I do believe,” my dad says. “In a lot of ways, he let everyone else’s addiction become his own.”

Matt hurt his back falling off a skateboard in elementary school and had to get surgery. Decades later, he collects welfare checks, reporting he can’t work because of his back pain. “The presence of a real injury is there, but, you know, also was the presence of an addictive personality,” my dad says.

There are many things Matt did that still stick with Morrigan. The biggest thing she remembers is random people surrounding her, constantly coming in and out of the house. “My little kid brain thought: Oh my god these are zombies. They looked terrifying,” says Morrigan.

Morrigan recalls one evening, a woman came in with her son, yelling about her and her partner getting into a domestic dispute. The couple, she believed, were friends of her dad’s. “The son was older than me. He looked absolutely terrified. So, four-year-old Mo offered him the Barbie that I had because he just looked so terrified about what was going on in his life,” says Morrigan. “And I was terrified because I was like, ‘Why is Matt around these people?’ She didn’t even knock. The door was always open. Anybody came in at any time.”

Today, Morrigan sees a therapist for the issues my uncle’s addiction caused that still affect her into adulthood. She is now a paramedic and on track to being an Intensive Care Unit (ICU) nurse. Working at hospitals sanctioned Morrigan’s further understanding of how her father’s and our cousin's addiction transpired. “I definitely think the time that Alisha and Matt really got into drugs was when the first-rate, go-to for all physicians, was offering those pain medications,” says Morrigan. “Even now, we’re still seeing many people come in for chronic pain. Like, if you look in the doctor's offices you can see that there’s a sign, in mine specifically, that ended chronic pain management. You have to go be evaluated somewhere else.”

According to Morrigan and I’s uncle, starting around the late-90s and early-2000s, chronic pain was simply being treated with pain pill prescriptions in Chesapeake. “Doctors was prescribing these pain pills and these opioids for anyone who’d come in there with a hard-luck story: ‘Oh, my knee’s hurting. Oh, my back’s hurting.’ This and that. And they loaded the market with opioids,” says Uncle Tommy. His wife, my aunt Donna, was prescribed OxyContin for her cancer pain. “Aunt Donna got ‘em and she tried ‘em and she went back to ask for something else,” Uncle Tommy says. “Because a lot of these people–due to injuries, surgeries, cancer, back problems and operations–they were getting hooked on these pain pills because they was easy to get. Doctors was prescribing them.”

Drug distributors hired sales representatives to advertise the drugs they were selling, giving incentives to doctors to write more prescriptions. “These doctors, if they prescribe so much pills per month to these people, they’d give ‘em cruises. They’d pay ‘em money or take ‘em on trips,” says Tommy. “I remember when I would go to the doctor, them drug reps would come in there and offer ‘em stuff like that for prescribing these pills.”

Business strategies like these are what eased the overprescribing of pain pills to citizens in small-town America. Labor-driven communities were perfect for big pharmaceutical companies, drug distributors, doctors and pharmacists to use as the target consumers for their product as these people held physically demanding jobs that often led to work injury.

“It started from that [chronic pain management] and you also have the coal mines up there and that’s a very physically, hard-on-the-body way of life so any sort of pain or ailment that I’m assuming they went to a doctor for, they were just like ‘Oh! Here’s some Norco, here’s some hydrocodone,’” says Morrigan. “They’re very easily addictive. So, when they realized that you could get it on the streets, or you could sell it, it started a whole pandemic by these pharmaceutical companies that started through physicians and trickled down.”

Legal Action

In the 2007 U.S. Supreme Court case, Harrington v. Purdue Pharma L.P., documents show Purdue’s awareness of the risks of OxyContin. “Internal documents revealed through lawsuits exposed that Purdue executives were aware of high abuse rates but continued marketing opioids aggressively,” says Dr. Manne.

Purdue granted promotions to sales representatives who made big deals in selling OxyContin to drug distributors and doctors. They created friendships with their clients and gave them incentives for selling their product, such as cruises and concert tickets. Pharmacies profited as well, turning a blind eye when fulfilling pain pill prescriptions at alarming numbers.

Through this chain of supply, drug producers, drug distributors, doctors and pharmacies demolished labor-driven communities in West Virginia. The town of Chesapeake, once a thriving coal mining town, now looks unrecognizable to my uncle Tommy after the influence of drugs. Uncle Tommy has watched the result of corporate abuse from pharmaceutical companies first-hand. Having been a coal miner himself, he noticed a shift in the way work injury for miners was treated. “A lot of people had pain or would get hurt on the job–occupational injury–and the first thing they’d want to prescribe them is OxyContin,” says Uncle Tommy.

There have been some reparations for the damage caused to the citizens of West Virginia. According to a 2006 law review by Joseph B. Prater, former West Virginia attorney general, Darrell McGraw, sued Purdue Pharma in 2001 for the over promotion and distribution of OxyContin in West Virginia. The settlement resulted in a small sum of $10 million to go towards doctor continuing education programs, law enforcement drug prevention programs and community drug-rehabilitation programs. Not nearly enough to get the state to bounce back.

In a lawsuit closely reported by Eric Eyre of the Charleston-Gazette Mail, the state of West Virginia sued Cardinal Health, AmerisourceBergen, and a dozen other prescription drug distributors. The West Virginia lawsuit came to a settlement of $20 million from Cardinal Health, $16 million from AmerisourceBergen, and an additional $11 million allotted from previous settlements from nine smaller distributors–amounting to $47 million. The settlement brought federal recognition to the case, prompting the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) to release detailed records to the public of all the distributors' pill sales.

Reports showed drug distributors had shipped 76 billion oxycodone and hydrocodone from 2006 to 2012. West Virginia along with Kentucky, South Carolina and Tennessee were among the states with the highest concentration of pills per person. Between 2007 and 2012, 119 million doses of highly addictive drugs were shipped to pharmacies across the state by AmerisourceBergen alone.

West Virginians filed civil and class action lawsuits against drug distributors either for their own addictions or for the addiction of a loved one who passed away– but no amount of money could reverse the damage. “I’ve had so many people talk to me about Big Pharma tell me to get a lawsuit going. You be a participant. You could just sit back and we’ll take care of everything,” says my cousin Mary who lost her son. “But, I just couldn’t bring myself to be a part of these lawsuits because the pain was too much.”

The pain of West Virginians has long been overlooked. Even as pills were excessively prescribed–intending to relieve pain–communities were consumed in a dependency created by drug corporations abusing their power.

Path to Recovery

10 years later, my cousin, Mary Stanley, says she has started to heal after losing her son Eric. “The pain is always going to be there of losing a child. But, it doesn’t always go back to the day that it happened,” Eric’s mother says. “I can smile again. I can laugh again. I’m not so anxious all the time. But, I’m not saying the hole in my heart will ever ever close.”

Mary Stanley sitting at her mother’s, my great-aunt Rosie’s, dining room table in Huntington, WV, on January 7, 2025.

Tori, Eric’s sister, is now sober and a dedicated mother to her kids John Christian, 12, and Gage, 8. Tori believes open-communication with her children about the realities of drugs serves as the most important way to combat the devastation in Huntington so that patterns aren’t repeated. “I’ve been very blunt with my oldest son about what has went on because, it didn’t only go on with me, it went on with his dad,” says Tori about Christian’s father who sold my cousin Eric the drugs that killed him. Christian’s father was in jail for a decent part of his early life for drug-related crimes. “So, he’s had to have some type of answers,” Tori explains. “I had to be honest with him in hopes that he sees how bad that has hurt him, and hope that would inspire him not to want to go down the same path me and his dad did.”

Tori Stanley sits in her grandmother’s, my great-aunt Rosie’s, bright yellow dining room in Huntington, WV, on January 7, 2025.

Mary agrees with her daughter Tori when she says communication with the youth is essential to communities dealing with the aftermath of the opioid epidemic. “When it comes to people’s minds, we have to get to them early enough. Open your eyes and say exactly what’s going on and don’t sugarcoat it. You go and talk to these kids and tell it like it is,” says Mary. “The earlier the better. And, by the time they get to middle school or start high school, they’ll be like ‘Remember that woman who almost cried because she was telling us what was going on? That affected me.’”

My cousins Layne, 11, and Layla, 11, Darla and Donnie’s grandchildren, have grown so much since I last saw them at my family’s house in North Carolina. Their grandmother says Layne is still the quiet boy I remember and Layla is growing up to be a young lady. The twins now live in Louisiana after their adoption was turned over to their biological father’s sister. “We loved them. We really enjoyed them,” Darla says. Their grandparents still get to see them on holidays, building new memories with the children and, when they’re away, remembering the good times they spent when the twins were in their custody. “I’d always get so tickled at Layla, when I would bring them home from school. She would open the door and say ‘I here Mamaw!’ And that was the most pleasing sound,” Donnie says.

Layla and I doing each other’s makeup in my childhood bedroom in Waxhaw, NC, on December 28, 2018.

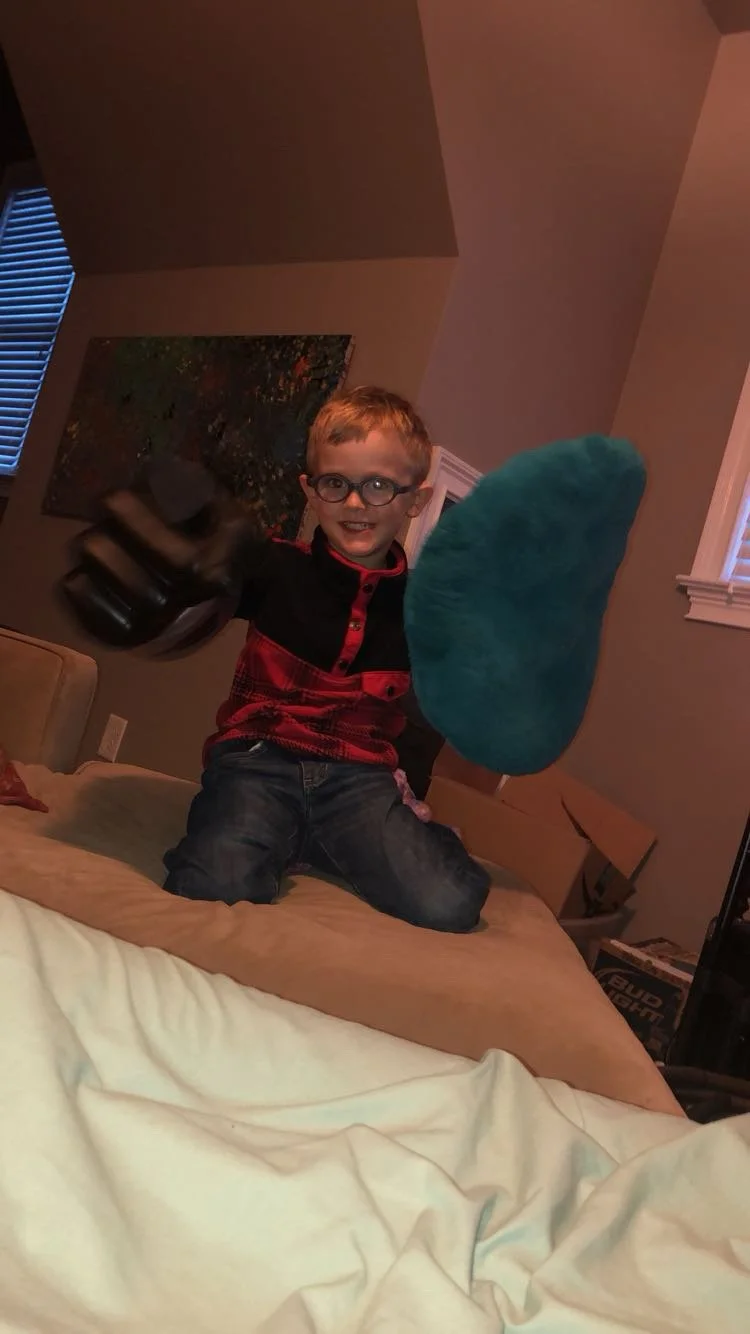

Layne standing his ground with a foam Carolina Panthers “Keep Pounding” fist and a pillow for a shield at my family’s home in Waxhaw, NC, on December 31, 2018.

Great-Aunt Darla pointing to how big the twins have grown from their height marks on the wall at her home in Kanawha City, WV, on January 4, 2025.

The distance my cousin Morrigan was able to get from her biological father helped tremendously. Moving to North Carolina with her mother, stepdad and half-brother allowed her to have a shot at a stable family life. “I’ve learned that just because he and I share the same DNA, doesn’t mean I have to speak to him, I have to be like him, I have to be around him. It’s starting to feel like, even though he’s alive, that his presence–his ghost–doesn't haunt me anymore,” says Morrigan.

Recently, she has been in better contact with Matt’s other children, my first cousins Little Matt, 20, and Maddie, 17, who still live in West Virginia with each of their mothers. Even though they never lived together and each experienced their father’s addiction at different stages, they discuss together the discomfort he created and how they’ve started to work through it. “It may have taken us a while for, like with things that make us uncomfortable, to realize we don’t have to put up with that,” says Morrigan. “It definitely affected my ability to stand up for myself and I’m getting a lot better at that.”

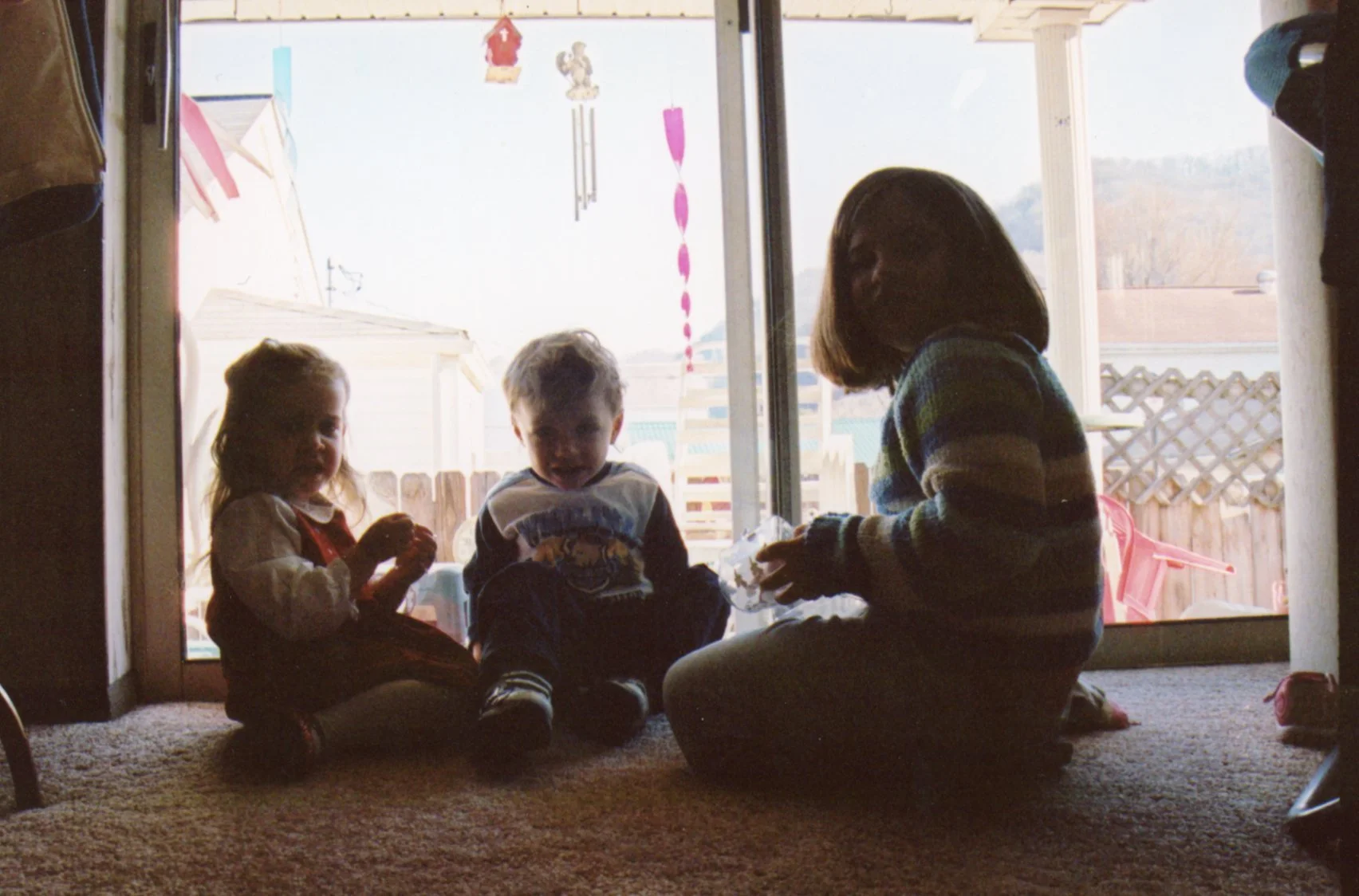

Me, Little Matt and Morrigan (in order from left to right) sit in the light shining in from my grandparents’ porch on the carpet of the living room floor in Chesapeake, WV, around Christmas time. Photo provided by my mother, Amy Hively.

As opioid addiction and overdose begin to decline, the damages that Big Pharma caused are not over. The impacts left by corporate exploitation still prevail over West Virginia’s people. These issues caused generational impacts on my West Virginian family and others like them, more recently with big drug companies– but beginning with the coal companies who created a reliance and dependence on their jobs.

For over a century, the suffering of West Virginians, as a result of abusive practices of neglect and greed, has long been overlooked. America’s economy and industrial assets were built off the backs of miners. Mining is what fueled the American economy and sparked our nation’s industrial growth. Coal generates electricity, but it is also a key ingredient for steelmaking. My uncle Tommy says when U.S. steel mills in places like northern West Virginia and Pennsylvania dried up and trade turned to cheaper, foreign steel, coal mines were the next to go. “From the 1920s to the 80s, West Virginia was a coal-driven economy,” says Uncle Tommy. “Now they’re trying to diversify into tourism.”

West Virginia is a beautiful state. The rural mountains provide picturesque scenes of nature and serenity. Historically, however, the state’s rural and isolated qualities allowed the rest of America to presume the state as culturally backward in outside representation, according to historian Ronald L. Lewis. Stereotypes like the ‘hillbilly,’ emphasized in American literature and Hollywood, have long since painted West Virginians in a negative light– making them out to be unintelligent, lazy and out-of-touch with the rest of society. “The old saying was, we had one leg shorter than the other because from walking on the hill you’d walk sideways,” says my great aunt Rosie. “Then there was barefoot and pregnant. That one was always said, and it really really bothers me.” Present day, West Virginians are still portrayed in a negative way in popular culture. Aunt Rosie refers to the AllState commercial aired during the 2024 college football season. Yet again, West Virginians are put on display to be seen by the rest of the country as less intelligent. “They could have picked any other school,” says Rosie. “It’s just cruel.”

A 2004 study by Bill Barker called “A Study of West Virginia Values and Culture,” found West Virginians tend to hold values in heritage, individuality, hospitality, faith and hard work. “Most miners have an excellent work ethic,” says my uncle Tommy, a retired miner. In 2006, Cathy Coyne and other researchers conducted a public health study called: “Social and Cultural Factors Influencing Health in Southern West Virginia: A Qualitative Study.” Here, it was found that West Virginians have come to embrace the term ‘hillbilly,’ taking it back out of pride for their background and culture. My West Virginia family members identify with this term overall, always saying “hillbilly” out of a sense of pride for where they are from. My father’s side often calls us the “Hillbilly Hively’s.”

Despite misconception and misrepresentation surrounding West Virginians and their given circumstances, they remain strong– working through the generational trauma caused by both the coal and drug industries. The effects caused by a vicious cycle of corporate abuse and dependency still linger on both sides of my family and West Virginian families alike. More awareness of the geographical disparity that plagues the West Virginia people, whose livelihoods have been rooted in the state for generations, can only help in the Mountain State’s path to recovery. It must be understood that these contemporary issues did not appear from nowhere. It’s arguable that it was like this from the beginning–since corporations first began profiting from West Virginia resources.